Attachment styles are patterns of behavior and beliefs about relationships that develop in childhood and continue throughout adulthood. These styles greatly affect our relationships, emotional health, and overall happiness.

Table of Contents

What Is Attachment Style?

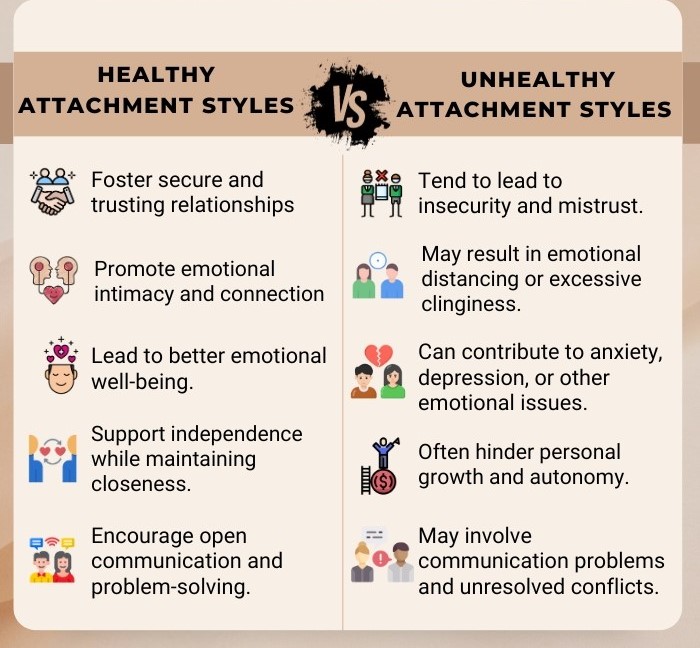

Attachment style refers to the way individuals form emotional bonds and connections 1 Moghadam, M., Rezaei, F., Ghaderi, E., & Rostamian, N. (2016). Relationship between attachment styles and happiness in medical students. Journal of family medicine and primary care, 5(3), 593–599. https://doi.org/10.4103/2249-4863.197314 with others, and it is often based on early experiences with caregivers. The types of attachment styles can be both positive and negative, depending on how they impact individuals’ relationships. Secure and healthy attachment styles bring about successful relationships, whereas unhealthy attachment styles lead to negative consequences for our mental health.

The concept of attachment style originated from the work of John Bowlby, a British psychologist, and Mary Ainsworth, an American-Canadian psychologist, who conducted pioneering research on the attachment behaviors of infants and children in the 1950s and 1960s.

They identified three primary types of attachment styles in their pioneering “Attachment Theory” 2 Cassidy, J., Jones, J. D., & Shaver, P. R. (2013). Contributions of attachment theory and research: a framework for future research, translation, and policy. Development and psychopathology, 25(4 Pt 2), 1415–1434. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579413000692 : secure, anxious-ambivalent, and avoidant. Later research has expanded upon these categories to four attachment styles including the disorganized and fearful-avoidant type.

Read More About Attachment Theory Here

Depiction Of Attachment Styles In Movies

The types of attachment styles in movies are often portrayed through character evolution, interactions, relationships. For instance, Matthew Perry’s Chandler Bing in the hit-sitcom FRIENDS (1994-2004) displays an anxious and obsessive attachment style whereas Matt Le Blanc’s Joey Tribianni shows an avoidant attachment style.

The characters of Roderick and Madeline Usher in Netflix’s The Fall Of The House Of Usher (2023) exhibit a secure but obsessive attachment style in relationships. Conversely, the characters of the twins Miles and Flora in the horror classic The Turn Of The Screw (1898) display a fearful and avoidant attachment style and mental health issues that come with exposure to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs).

The Four Types Of Attachment Styles

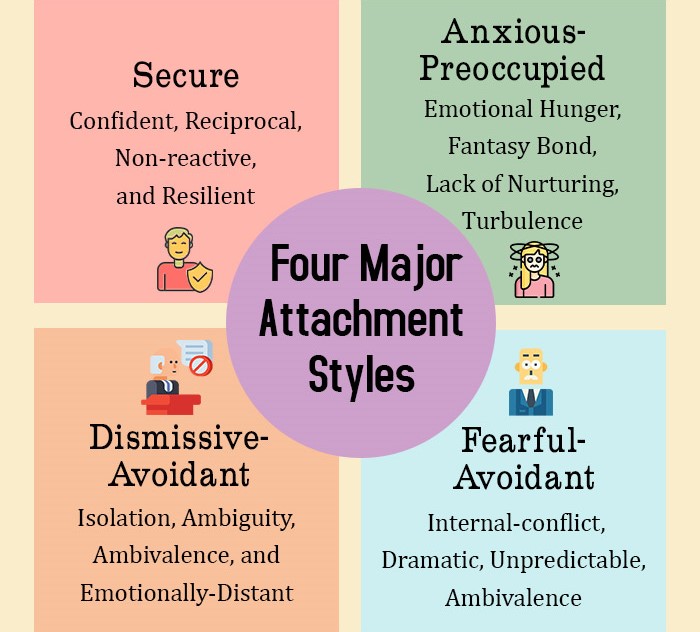

Research 3 Sheinbaum, T., Kwapil, T. R., Ballespí, S., Mitjavila, M., Chun, C. A., Silvia, P. J., & Barrantes-Vidal, N. (2015). Attachment style predicts affect, cognitive appraisals, and social functioning in daily life. Frontiers in psychology, 6, 296. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00296 categorizes the 4 types of attachment styles into the following:

The four attachment styles are:

1. Secure Attachment Style

Individuals with a secure attachment style tend to feel comfortable with emotional intimacy, trust others, and have positive expectations of relationships. They can effectively regulate their emotions and seek support from others when needed. For example, a child with a secure attachment style may feel comfortable exploring their environment and interacting with strangers when their caregiver is present.

2. Anxious-Ambivalent Attachment Style

Individuals with an anxious attachment style or anxious-ambivalent attachment style often fear abandonment and have negative expectations of relationships. They may become clingy and overly dependent on their partners, seeking constant reassurance and validation. For example, a child with an anxious-ambivalent attachment style may become distressed when their caregiver leaves and may seek proximity and attention upon their return.

3. Avoidant Attachment Style

Individuals with an avoidant attachment style tend to be emotionally detached, self-reliant, and uncomfortable with intimacy. They may avoid close relationships and may struggle to express their emotions. For example, a child with an avoidant attachment style may appear indifferent or detached when their caregiver leaves or returns, and may not seek comfort or reassurance.

4. Disorganized/Fearful-Avoidant Attachment Style

Individuals with a disorganized attachment style or fearful-avoidant attachment style may display contradictory behaviors and emotions, such as appearing anxious and fearful while also attempting to avoid their attachment figures.

This style is often associated with experiences of trauma or abuse in early childhood. For example, a child with a disorganized/fearful-avoidant attachment style may exhibit inconsistent or erratic behaviors in the presence of their caregiver, such as freezing or exhibiting aggressive behaviors.

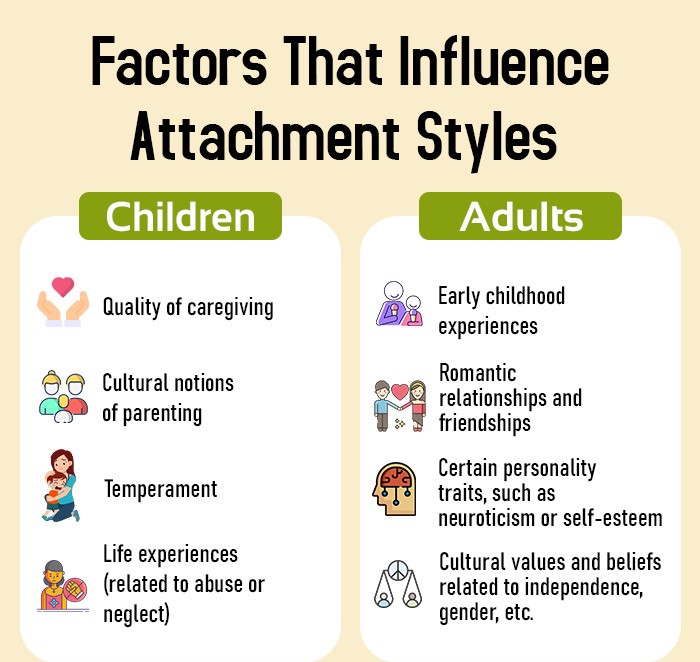

Factors That Influence Attachment Styles

Certain factors 4 Darban, F., Safarzai, E., Koohsari, E., & Kordi, M. (2020). Does attachment style predict quality of life in youth? A cross-sectional study in Iran. Health psychology research, 8(2), 8796. https://doi.org/10.4081/hpr.2020.8796 influence the development of attachment patterns in childhood and adulthood, including:

- Parental sensitivity and responsiveness, particularly maternal-infant childhood attachment

- Quality of caregiving

- Early life and developmental experiences (related to trauma, separation from a caregiver, etc.)

- Genetic predisposition or innate inclination toward certain attachment patterns

- Temperament and personality traits

- Cultural norms and values (associated with independence, interdependence, collectivism, etc.)

- Later life experiences (such as romantic relationships and friendships)

Attachment Style And Mental Health

The four attachment styles have a significant impact on a person’s mental health. People with a healthy and positive attachment style in relationships are generally associated with sound mental health and reduced risks of mental health disorders 5 Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2012). An attachment perspective on psychopathology. World psychiatry : official journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 11(1), 11–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wpsyc.2012.01.003 like depression and anxiety.

In contrast, a negative attachment style—characterized by clinginess, fear of abandonment, and overreliance on others for validation—may have negative consequences for relationships, leading to feelings of insecurity and dependence.

Similarly, an avoidant attachment style, characterized by emotional detachment, can lead to difficulties in forming and maintaining close relationships. Individuals with these negative types of attachment styles are more likely to have poor mental health and tend to be at a higher risk of mental health disorders like borderline personality disorder, dependent personality disorder, and so forth.

Read More About Dependent Personality Disorder Here

Role Of Attachment Style In Relationships

Attachment styles can have a significant impact on individuals’ adult relationships, 6 Simpson, J. A., & Steven Rholes, W. (2017). Adult Attachment, Stress, and Romantic Relationships. Current opinion in psychology, 13, 19–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.04.006 shaping their ability to connect with others and maintain healthy relationships. For instance, individuals with a secure attachment style tend to have healthy and positive relationships, characterized by trust, emotional intimacy, and effective communication. They are more likely to have successful romantic relationships and tend to experience greater satisfaction and happiness in their relationships.

Read More About Stress Here

In sharp contrast, individuals with an anxious-ambivalent attachment style struggle in adult relationships—becoming overly dependent on their partners, and experiencing jealousy, fear of abandonment, and emotional volatility.

They are more likely to engage in dysfunctional relationship behaviors, such as pushing partners away, becoming clingy, or engaging in relationship drama. Similarly, individuals with a disorganized/fearful-avoidant attachment style may experience difficulties in adult relationships due to their inconsistent and erratic behaviors, trust issues, relationship insecurity, and difficulties with intimacy.

On the other hand, individuals with an avoidant attachment style also struggle with emotional intimacy and are less likely to seek out close relationships. They are more prone to engaging in casual relationships or avoiding relationships altogether. In romantic relationships, they struggle with expressing their emotions or connecting with their partners on a deeper level.

How To Regulate Your Attachment Style

Regulating attachment styles can be a challenging but important process for individuals seeking to develop healthier relationships and improve their overall well-being. Consider the following strategies 7 van der Meer, L. B., van Duijn, E., Giltay, E. J., & Tibben, A. (2015). Do Attachment Style and Emotion Regulation Strategies Indicate Distress in Predictive Testing?. Journal of genetic counseling, 24(5), 862–871. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-015-9822-z to develop a healthy attachment style:

- Practice self-awareness. Recognize and understand your attachment style and identify related behavior and emotions.

- Challenge negative thought patterns and replace them with positive and realistic beliefs to regulate the 4 types of attachment styles and improve relationships.

- Seek a therapist to address underlying mental health issues and develop healthier relationship patterns.

- Practice mindfulness and stress management techniques like meditation or deep breathing to regulate emotions and reduce stress.

- Develop healthy coping mechanisms such as exercise, journaling, or spending time with supportive friends and family.

- Engage in healthy relationships to reinforce secure attachment patterns.

- Communicate healthily with the members of your support system—be it family or friends.

Read More About Mindfulness Here

Takeaway

Childhood attachment is a crucial coping mechanism for infants as it helps them form a mental representation of their caregiver, which enables them to explore the world without becoming distressed. Therefore, it is vital for parents to provide a nurturing environment that fosters secure attachment to promote healthy development and ensure their child grows up to become a responsible and emotionally stable adult.

At A Glance

- Attachment style refers to the way individuals form emotional bonds and connections with others based on early experiences with caregivers.

- There are four attachment styles: secure, anxious-ambivalent, avoidant, and disorganized/fearful-avoidant.

- Attachment style and mental health are intricately related.

- Attachment style in relationships can have a significant impact on individuals’ well-being.

- To regulate the 4 types of attachment styles, it is essential to practice self-awareness, challenge negative thought patterns, and practice mindfulness and stress management techniques.

- Unhealthy attachment styles and attachment issues can be effectively addressed with therapies and medication.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What attachment style is most common?

The most common of the four attachment styles is secure attachment.

2. Can you have multiple attachment styles?

Out of the 4 types of attachment styles, the anxious attachment style is often associated with jealousy.

3. Which attachment style is most jealous?

Out of the 4 types of attachment styles, the anxious attachment style is often associated with jealousy.

4. Which attachment style is needy?

The anxious attachment style is often associated with being needy.

5. Which factors are responsible for problematic attachment styles?

Factors such as childhood experiences, parental relationships, and past trauma can contribute to any problematic attachment style and mental health issues.

6. Where do attachment styles come from?

Our childhood attachment or the earliest intimate relationships with caregivers usually shape the development of our attachment styles.