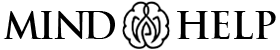

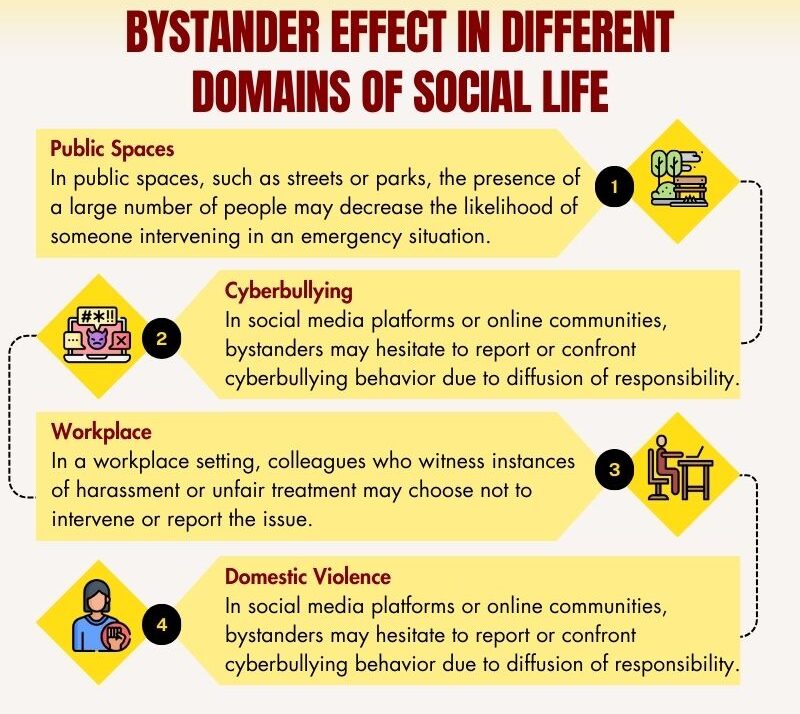

The bystander effect refers to a phenomenon where the presence of a larger number of people reduces the likelihood of individuals helping someone in need. In emergency situations, people are more inclined to take action when there are fewer or no other witnesses present.

What Is The Bystander Effect?

The bystander effect is a social psychological phenomenon that refers to the tendency of individuals to be less likely to offer help or intervene in an emergency situation when other people are present. It suggests that as the number of bystanders increases, the likelihood of any one individual offering assistance decreases.

This phenomenon was first brought to public attention and extensively studied following the infamous case of the murder of Kitty Genovese in 1964. Following the Genovese case, social psychologists Bibb Latané and John Darley conducted a series of experiments 1 Hortensius, R., & de Gelder, B. (2018). From Empathy to Apathy: The Bystander Effect Revisited. Current directions in psychological science, 27(4), 249–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721417749653 to understand the underlying processes of the bystander effect.

In one classic study, they staged simulated emergencies and found that participants were less likely to help when they believed other bystanders were also present. This suggested that the presence of others diffused responsibility and created a diffusion of moral responsibility, leading to a decreased likelihood of intervention.

How Do Emotions Affect The Bystander Effect?

Since the initial research on the bystander effect, subsequent studies have further explored the emotional conditions under which the effect is more or less likely to occur. Factors 2 Liebst, L. S., Philpot, R., Bernasco, W., Dausel, K. L., Ejbye-Ernst, P., Nicolaisen, M. H., & Lindegaard, M. R. (2019). Social relations and presence of others predict bystander intervention: Evidence from violent incidents captured on CCTV. Aggressive behavior, 45(6), 598–609. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21853 such as the perceived costs and benefits of helping, the relationship between the bystander and the victim, and the presence of other bystanders who are taking action can all influence whether an individual is more likely to intervene in an emergency.

Characteristics Of The Bystander Effect

The common markers 3 Mitchel R. E. (2004). The bystander effect: recent developments and implications for understanding the dose response. Nonlinearity in biology, toxicology, medicine, 2(3), 173–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/15401420490507512 of bystander effect include:

- Diffusion of responsibility: Bystanders feel less responsible to help when others are present.

- Pluralistic ignorance: Bystanders look to others for cues on how to behave.

- Decreased likelihood of intervention: More bystanders, less help offered.

- Social influence: Bystanders are influenced by others’ behavior.

- Perceived costs and benefits: Bystanders consider the risks and rewards of helping.

- Relationship with the victim: Personal connection increases the likelihood of helping.

- Presence of other helping bystanders: If some help, others are more likely to join.

Case Examples Of The Bystander Effect

The murder of Kitty Genovese in New York in 1964 remains the most prominent 4 Mercer Kollar, L. M., Peng, L., Ports, K. A., & Shen, L. (2020). Who Will be a Bystander? An Exploratory Study of First-Person Perception Effects on Campus Bystander Behavioral Intentions. Journal of family violence, 35(6), 647–658. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-019-00054-2 of all examples of the bystander effect. During the early hours of March 13, 1964, Kitty Genovese, a 28-year-old bartender living in the Kew Gardens neighborhood of Queens, New York, was raped and stabbed near the entrance to her apartment building.

An article in The New York Times, published two weeks after the murder, claimed that 38 witnesses in the apartment building witnessed the incident but none called the police or aided Genovese during the fatal attack. This case brought attention to the phenomenon and sparked research into bystander behavior.

Another example of the bystander effect is the death of Tagonoura, a junior high school student in Japan in 2011. He was assaulted seriously in a public space, subsequently dying due to complications from his injuries.

The incident occurred in a crowded train during rush hour, with many passengers witnessing the assault but failing to intervene or seek help. This case highlighted the significance of the bystander effect in our daily lives and led to discussions about social responsibility and intervention in emergencies.

Possible Causes Of The Bystander Effect

Despite research, the understanding of the bystander effect remains sketchy. Over the years, experts 5 Mercer Kollar, L. M., Peng, L., Ports, K. A., & Shen, L. (2020). Who Will be a Bystander? An Exploratory Study of First-Person Perception Effects on Campus Bystander Behavioral Intentions. Journal of family violence, 35(6), 647–658. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-019-00054-2 have tried to decode answers to the question “How do emotions affect the bystander effect?”. Emerging studies 6 Scaffidi Abbate, C., Misuraca, R., Vaccaro, C., Roccella, M., Vetri, L., & Miceli, S. (2022). Prosocial priming and bystander effect in an online context. Frontiers in psychology, 13, 945630. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.945630 , however, claim how the following factors influence the psychological effects experienced by bystanders:

- Lack of responsibility for the respective victim

- Lack of social cues from bystanders to help the victim

- Difficulty in interpreting the situation accurately, causing hesitation or inaction

- Feelings of being unqualified or uncertain about how to provide effective help

- Fear of taking incorrect action or making the situation worse for the victim

- Hesitancy to stand out or draw attention to themselves by taking action

- The bystanders’ distress and fear of the negative consequences associated with their providing help.

Impact Of The Bystanders Effect On Daily Functioning

The bystander effect leads to a decreased likelihood of individuals offering help or intervening, potentially prolonging emergency situations and eroding trust in others. It affects individuals 7 Hall E. J. (2003). The bystander effect. Health physics, 85(1), 31–35. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004032-200307000-00008 in social situations by:

- Reducing intervention in emergencies

- Making it more difficult to seek assistance

- Influencing social norms of inaction

- Diminishing collective responsibility

- Hindering prosocial behavior

- Impacting well-being and trust

The Bystander Effect And Mental Health

The bystander effect and mental health of the victims are intricately related. The psychological effects experienced by bystanders can have significant implications 8 Scott, E. S., Ross, D. A., & Fenstermacher, E. (2021). Stand By or Stand Up: Exploring the Biology of the Bystander Effect. Biological psychiatry, 90(2), e3–e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2021.05.007 for the mental health of the victims involved:

1. Feelings of isolation :

The victims of the bystander effect may experience a sense of isolation and abandonment, as they expected help from others but did not receive it. This can lead to feelings of loneliness, helplessness, and even betrayal.

Read More About Loneliness Here

2. Increased distress :

When individuals in distress do not receive immediate assistance, their distress levels may intensify. They may feel heightened fear, anxiety, or panic due to the perceived lack of support and the belief that nobody cares about their well-being.

Read More About Fear Here

3. Reduced self-esteem :

Victims of the bystander effect may internalize the lack of help as a reflection of their own worth or importance. They may question their own value, leading to diminished self-esteem and self-confidence.

Read More About self-esteem Here

4. Post-traumatic stress symptoms :

For individuals who have experienced a traumatic event and did not receive help from bystanders, the aftermath can be particularly distressing. They may develop symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) 9 Janson, G. R., & Hazler, R. J. (2004). Trauma reactions of bystanders and victims to repetitive abuse experiences. Violence and victims, 19(2), 239–255. , such as intrusive thoughts, nightmares, flashbacks, and hypervigilance.

Read More About PTSD Here

5. Trust issues :

Being let down by bystanders during a time of need can erode an individual’s trust in others and the belief that people can be relied upon for support. This can lead to difficulties in forming and maintaining relationships and increased skepticism about seeking help in the future.

6. Social withdrawal :

Victims of the bystander effect may withdraw from social situations or avoid seeking help altogether due to the fear of being ignored or rejected. This can further isolate them and hinder their ability to receive the necessary support for their mental health.

How To Overcome The Bystander Effect

Measures as to how to overcome or reduce the bystander effect is tricky. Common strategies 10 Fischer, P., Krueger, J. I., Greitemeyer, T., Vogrincic, C., Kastenmüller, A., Frey, D., Heene, M., Wicher, M., & Kainbacher, M. (2011). The bystander-effect: a meta-analytic review on bystander intervention in dangerous and non-dangerous emergencies. Psychological bulletin, 137(4), 517–537. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023304 via which individuals can counteract the bystander effect and create a more supportive and compassionate society include:

- Raising awareness about the bystander effect

- Assuming personal responsibility for helping others

- Being proactive in offering assistance

- Seeking social support

- Trusting your instincts during an emergency situation

- Overcoming social barriers

- Cultivating empathy and perspective-taking

- Acquiring CPR (Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation) and first aid training

- Encouraging a culture of responsibility and collective well-being

Takeaway

It is crucial to recognize that we possess the power to transcend the bystander effect and extend a helping hand to those in need. By fostering connections with our neighbors, being vigilant about their well-being, and engaging in open communication with fatigued or troubled colleagues, we can make a positive impact.

Taking the time to listen and understand people’s stories and actively participating as volunteers can also contribute to our own well-being. Remarkably, performing acts of kindness activates the reward system in our brains, while simultaneously reducing stress-related brain activity. Therefore, by aiding others, we not only benefit them but also experience personal rewards and alleviate our own stress levels.

At A Glance

- The bystander effect is a social psychological phenomenon where individuals are less likely to help in emergency situations when others are present.

- Factors such as diffusion of responsibility, pluralistic ignorance, and social influence comprise common causes of the bystander effect.

- Notable examples of the bystander effect include the cases of Kitty Genovese and Tagonoura.

- The bystander effect can negatively impact daily functioning by reducing intervention and hindering prosocial behavior.

- In victims, it can lead to feelings of isolation, increased distress, reduced self-esteem, post-traumatic stress symptoms, trust issues, and social withdrawal.

- To overcome the bystander effect, strategies include raising awareness, assuming personal responsibility, being proactive, seeking social support, etc. can be helpful.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Do bystanders have a responsibility to intervene?

Yes, bystanders have a responsibility to intervene if they can safely do so.

2. Do bystanders feel guilty?

Bystanders may feel guilty if they fail to intervene or help in an emergency situation.

3. What are the obstacles to bystanders intervening in an emergency?

Obstacles to bystander intervention in an emergency can include fear, uncertainty about how to help, diffusion of responsibility, and concerns about personal safety.