Self-harm, a prevalent behavior of self-injury, is observed across various age groups. Although self-harm is not typically driven by suicidal intent, it is often considered a symptom of underlying psychiatric conditions. In some cases, self-harm increases the risk of mental health conditions.

What Is Self-Harm?

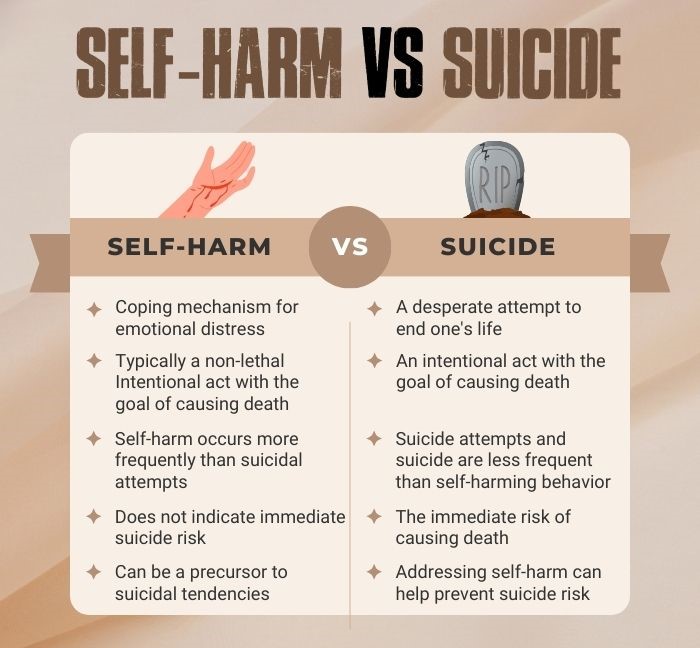

Self-harm (SH), also known as self-injury, encompasses a range of intentional behaviors that vary in severity, from milder acts associated with emotional distress to more severe actions that closely resemble suicidal tendencies [mfn] Klonsky, E. D., Victor, S. E., & Saffer, B. Y. (2014). Nonsuicidal self-injury: what we know, and what we need to know. Canadian journal of psychiatry. Revue canadienne de psychiatrie, 59(11), 565–568. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371405901101 [/mfn] .

Prevalence Of Self-Harm

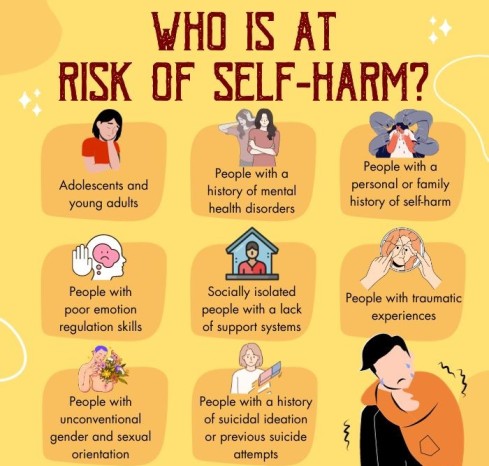

Studies show that women and men equally show signs of self-harm. However, women are more prone to cutting and men to hitting and burning. A previous study suggests that the life-time risk of self-injury is ~1:7 for women and ~1:25 for men [mfn] Klonsky, E. D., Victor, S. E., & Saffer, B. Y. (2014). Nonsuicidal self-injury: what we know, and what we need to know. Canadian journal of psychiatry. Revue canadienne de psychiatrie, 59(11), 565–568. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371405901101 [/mfn]. Research also shows that self-harm tendencies appear to be more common among LGBTQ+ people who report non-heterosexual orientations.

Self-harm is rare in children, most common in adolescents and young adults [mfn] Bailey, D., Wright, N., & Kemp, L. (2017). Self-harm in young people: a challenge for general practice. The British journal of general practice : the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 67(665), 542–543. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp17X693545 [/mfn], and not so much in adults. However, self-harm tends to show relapses in the elderly population and the mentally ill. Because numbers can not be ascertained in research concerning SH (as most SH cases are concealed), it has been difficult to gauge the rate of functioning recovery and relapses in SH.

Signs Of Self-Harm

The signs of self-harm can be classified [mfn] Lloyd-Richardson, E. E., Perrine, N., Dierker, L., & Kelley, M. L. (2007). Characteristics and functions of non-suicidal self-injury in a community sample of adolescents. Psychological medicine, 37(8), 1183–1192. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329170700027X [/mfn] as but not restricted to the following:

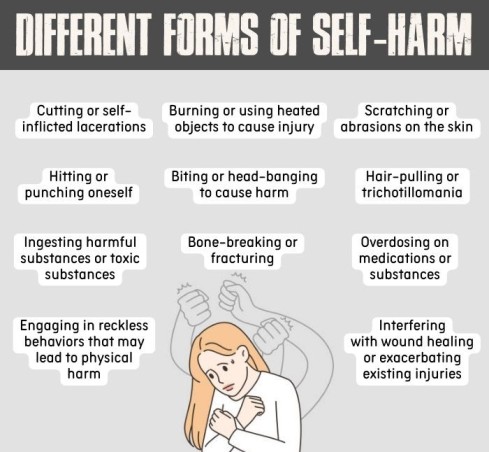

- Cutting and self-mutilation by a sharp object

- Self-mutilation by self-embedding of objects

- Tissue damage by excessive scratching, hitting, pulling, or burning

- Undertaking substance abuse or/and non-lethal overdoses (of alcohol, entertainment drugs, cannabis, over-the-counter prescription drugs)

- Undertaking willful ingestion of toxins (i.e., self-poisoning)

- Inflicting bodily harm by disordered eating (like bulimia and anorexia)

- Ideating suicide or showing signs of repeating suicidal attempts (in most severe cases)

What Causes Self-Harm?

Research [mfn] Miller, M., Redley, M., & Wilkinson, P. O. (2021). A Qualitative Study of Understanding Reasons for Self-Harm in Adolescent Girls. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(7), 3361. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073361 [/mfn] on what causes self-harm attributes the it to complex and multifaceted reasons. For many, self-harm is often perceived as:

- A coping mechanism for overwhelming emotions, offering temporary relief or a sense of control.

- Expression of distress or a means of communicating inner turmoil when verbalizing emotions is challenging.

- A form of self-punishment steaming from feelings of guilt, shame, or self-loathing.

- A release of tension or momentary distraction from emotional distress in mental health disorders.

- A means to release built-up tension from distorted thinking patterns.

- A means to regain a sense of control in overwhelming or powerless situations or in other aspects of their lives.

Mental Health Disorders Increase The Risk Of Self-harm

Several mental health conditions [mfn] Singhal, A., Ross, J., Seminog, O., Hawton, K., & Goldacre, M. J. (2014). Risk of self-harm and suicide in people with specific psychiatric and physical disorders: comparisons between disorders using English national record linkage. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 107(5), 194–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/0141076814522033 [/mfn] increase the risk of self-harm. These include:

1. Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD):

BPD is characterized by emotional instability, impulsivity, and difficulties in maintaining stable relationships. Signs of self-harm, including cutting, are often seen in individuals with BPD.

Read More About BPD Here

2. Depression:

Depression is a mood disorder characterized by persistent feelings of sadness, hopelessness, and a loss of interest in activities. Individuals with depression may engage in self-harm as a way to cope with emotional pain or as a manifestation of their inner turmoil.

Read More About Depression Here

3. Anxiety Disorders:

Various anxiety disorders, such as generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), social anxiety disorder (SAD), or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), can increase the risk of self-harm. The symptoms of this disorder can be overwhelming, and self-harm may be used as a coping mechanism to relieve anxiety or regain a sense of control.

Read More About Generalized Anxiety Disorder Here

4. Eating Disorders:

Eating disorders (such as anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, or binge-eating disorder) often exacerbate the risk of self-harm. Self-injury may be a means of expressing distress, self-punishment, or an attempt to gain control over body image and emotions.

Read More About Eating disorders Here

5. Substance Use Disorders:

Substance abuse and addiction can enhance the risk of self-harm behaviors as individuals may engage in self-injury while under the influence of substances or as a result of the emotional distress associated with their addiction.

6. Bipolar Disorder:

Bipolar disorder is characterized by extreme mood swings, including periods of mania and depression. During manic episodes, individuals may be more prone to engaging in impulsive and risky behaviors, including self-harm.

Read More About Bipolar Disorder Here

Diagnosing Non-suicidal Self-injury Disorder (NSSID)

Self-harm or non-suicidal self-injury disorder (NSSID) is diagnosed based on criteria [mfn] Zetterqvist M. (2015). The DSM-5 diagnosis of nonsuicidal self-injury disorder: a review of the empirical literature. Child and adolescent psychiatry and mental health, 9, 31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-015-0062-7 [/mfn] outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). To diagnose NSSID, mental health professionals look for recurrent intentional self-injury behavior on five or more days within a year, driven by a desire to relieve emotional distress or negative feelings. The self-injury must cause significant distress, impair functioning, or lead to medical complications, and it should not be accompanied by suicidal intent.

In addition to the DSM-5 criteria, clinicians may use clinical interviews, self-report measures, and assessments of associated mental health conditions to aid in the diagnosis of NSSID. Seeking professional help is crucial for an accurate diagnosis, appropriate treatment, and support for individuals experiencing non-suicidal self-injury behaviors.

Treatment For Self-Harm

Treatment for self-harm involves therapy, medication, or a combination of both [mfn] Bettis, A. H., Liu, R. T., Walsh, B. W., & Klonsky, E. D. (2020). Treatments for Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors in Youth: Progress and Challenges. Evidence-based practice in child and adolescent mental health, 5(3), 354–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/23794925.2020.1806759 [/mfn] in inpatient and outpatient mental health treatment programs. In the most severe cases, however, hospitalization and psychiatric admission should be sought to prevent acts of self-harm culminating into suicide or injury to others.

Therapies

Self-harm can be effectively managed by disciplined adherence to therapy (sometimes backed by medication) through inpatient and outpatient mental health treatment programs, safety planning, justice programs, youth access programs, support groups, etc. The most common interventions [mfn] Turner, B. J., Austin, S. B., & Chapman, A. L. (2014). Treating nonsuicidal self-injury: a systematic review of psychological and pharmacological interventions. Canadian journal of psychiatry. Revue canadienne de psychiatrie, 59(11), 576–585. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371405901103 [/mfn] used in the treatment for self-harm include:

- Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT)

- Integrated CBT (I-CBT)

- Mentalization-based treatment (MBT)

- Attachment-based family therapy (ABFT)

- Integrated family therapy

- Resourceful adolescent parent program (RAP-P)

- Intensive interpersonal psychotherapy for adolescents (IPT-A-IN)

- Multi-systemic therapy and psychiatric intervention

Medication

Self-harm is effectively managed by medication, backed by a disciplined adherence to therapy. As it is often associated with other mental disorders (like depression, spectrum disorders, dissociative disorders, personality disorders, etc.), medication [mfn] Smith B. D. (2005). Self-mutilation and pharmacotherapy. Psychiatry [Edgmont (Pa. : Township)], 2(10), 28–37. [/mfn] in the treatment for self-harm often involves antidepressants and medicinal drugs like flupentixol, clomipramine, duloxetine, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, olanzapine, and sertraline.

Awareness About Self-Harm

To destigmatize mental health issues and promote help-seeking for all mental disorders, including self-harm (SH), comprehensive psychoeducation initiatives [mfn] Leather, J. Z., O’Connor, R. C., Quinlivan, L., Kapur, N., Campbell, S., & Armitage, C. J. (2020). Healthcare professionals’ implementation of national guidelines with patients who self-harm. Journal of psychiatric research, 130, 405–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.08.031 [/mfn] and mental health awareness campaigns are vital. This involves collaborating with experts to develop crisis intervention programs and evidence-based resource guides accessible through community organizations, healthcare systems, welfare services, and justice programs.

In addition to distributing information, effective awareness campaigns should be implemented in educational institutions and other organizations, incorporating support mechanisms like hotline services, parenting skills training, mental health workshops, and group support programs. Furthermore, Self-injury Awareness Day (SIAD) on March 1 serves as a global effort to raise awareness [mfn] Son, Y., Kim, S., & Lee, J. S. (2021). Self-Injurious Behavior in Community Youth. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(4), 1955. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041955 [/mfn] and foster understanding about self-injury.

Helping Someone With Self-harming Behavior

Consider the following measures if you know someone [mfn] Hetrick, S. E., Subasinghe, A., Anglin, K., Hart, L., Morgan, A., & Robinson, J. (2020). Understanding the Needs of Young People Who Engage in Self-Harm: A Qualitative Investigation. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 2916. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02916 [/mfn] who displays signs of self-harms and want to help that affected person:

- Do not make panic, apparent assumptions, and judge people with self-harm tendencies. Instead, be empathetic and devise ways for effective communication to help.

- Listening, caring, understanding, and acceptance are the most helpful responses in these situations.

- Show concern for the injury and offer medical help.

- Encourage seeking medical help from mental health professionals.

- Acknowledge that living with self-harm and healing from it are difficult. Try to help during the therapy process, such as attending therapy sessions and providing affirmations.

Tips To Develop Coping Skills For Self-harm

Consider the following measures [mfn] Self-harm: assessment, management and preventing recurrence. (2022). In PubMed. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK588208/ [/mfn] if you think you have been experiencing self-injury tendencies and want to develop the coping skills for self-harm:

- Assess your thoughts and feelings about yourself

- Avoid stimulants that trigger your self-harm tendencies

- Develop substitution strategies to distract yourself from self-harm

- Talk to someone–face-to-face or online. It can be your family, a friend, a social worker, or a helpline

- Ask for psychiatric help[mfn] Fortune, S., Sinclair, J., & Hawton, K. (2008). Help-seeking before and after episodes of self-harm: a descriptive study in school pupils in England. BMC public health, 8, 369. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-8-369 [/mfn]

- Adhere to therapy and medication

- With safety planning, devise an emergency care plan

- Involve your loved ones in the therapy process

- Be patient and understand that healing from self-harm takes time

Nurturing Alternative Coping Skills For Self-Harm

People with self-harm tendencies should develop healthy and safe self-help strategies known as distraction or avoidance techniques/substitution coping strategies to cope with emotional distress. For instance, generating mindful ‘alternative behaviors’ like journaling, taking strolls, exercising or meditating, developing a new hobby, etc. can lead to recession of self-harm tendencies in sufferers.

Takeaway

Like diagnosis in any other mental health disorder, self-harm can be effectively managed by punctual and long-term adherence to therapy or medication or both. Remember that self-harm is indicative of graver underlying mental health disorders and suicidal intentions. To combat and prevent SH is to reduce greater risks involved.

At A Glance

- Self-harm is a common behavior of self-injury.

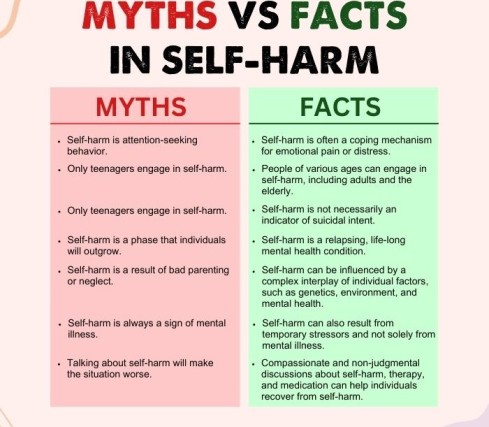

- Self-harm is neither enjoyable nor attention-seeking behavior.

- The common signs of self-harm include cutting and self-mutilation by a sharp object; tissue damage by excessive scratching, hitting, pulling, burning, etc.

- Self-harm stems mainly from mental health disorders and various other factors.

- People prone to self-harm should avail therapy, medication, and self-help mechanisms to combat self-harm.

- People providing help for self-harm should help in its combat by active participation and empathy.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How can I stop myself from self-harm?

To stop self-harm, it is important to seek professional help from therapists or counselors, build a support system, develop healthy coping mechanisms, and engage in activities that promote emotional well-being.

2. Why do so many young people self-harm themselves?

Many young people may self-harm as a coping mechanism for dealing with overwhelming emotions, mental health challenges, trauma, or a sense of lack of control in their lives.

3. Is self-harm normal behavior?

Self-harm is not considered a normal or healthy behavior; it often indicates underlying emotional distress or mental health issues and should be taken seriously.

Leave a Reply