Table of Contents

Attachment is a profound bond that develops between individuals over time, often starting in early childhood with parents or caregivers. It involves a sense of emotional connectedness and a desire for proximity to a particular person, known as the attachment figure.

What Is Attachment?

Attachment refers to the deep emotional bond that develops between individuals, especially between a child and their primary caregiver. The concept of attachment was first introduced by British psychoanalyst John Bowlby 1 Vicedo M. (2011). The social nature of the mother’s tie to her child: John Bowlby’s theory of attachment in post-war America. British journal for the history of science, 44(162 Pt 3), 401–426. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007087411000318 in the 1950s and has since been extensively studied in developmental psychology.

Attachment patterns can influence the way individuals interact with others in social and professional settings throughout their lives. These vary depending on the quality of caregiving 2 Benoit D. (2004). Infant-parent attachment: Definition, types, antecedents, measurement and outcome. Paediatrics & child health, 9(8), 541–545. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/9.8.541 that an individual receives in early childhood. Secure attachment is characterized by a sense of safety and trust in relationships, while insecure attachment can manifest in anxious or avoidant behaviors in relationships.

Examples of common attachment patterns in daily life include:

- A child seeking comfort from their parent when upset

- A partner seeking emotional support from their significant other

- A friend seeking reassurance from their close friend

- A child avoiding eye contact and physical touch from their caregiver

- A partner feeling uncomfortable with emotional intimacy and avoiding conversations

- A friend feeling anxious or jealous when his/her friend spends time with other people

- A person constantly seeking attention and validation from others

- A person being excessively critical and judgmental of themselves and others

Attachment Theory

Attachment theory is a psychological framework 3 Flaherty, S. C., & Sadler, L. S. (2011). A review of attachment theory in the context of adolescent parenting. Journal of pediatric health care : official publication of National Association of Pediatric Nurse Associates & Practitioners, 25(2), 114–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2010.02.005 that explains how the emotional bonds between individuals, especially between a child and their primary caregiver, can shape their social and emotional development throughout their lives.

Attachment theory emphasizes the importance of secure attachment, which is characterized by a sense of safety, trust, and emotional connection between individuals. The theory also describes various attachment styles, such as secure, anxious, avoidant, and disorganized attachment, which can develop depending on the quality of caregiving that an individual receives in early childhood.

The theory is used in various therapies (particularly attachment-based psychotherapy 4 Diamond, G., Diamond, G. M., & Levy, S. (2021). Attachment-based family therapy: Theory, clinical model, outcomes, and process research. Journal of affective disorders, 294, 286–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.07.005 ) that help individuals process past experiences and develop healthier patterns of attachment in their relationships.

Attachment Styles

The common 5 Sheinbaum, T., Kwapil, T. R., Ballespí, S., Mitjavila, M., Chun, C. A., Silvia, P. J., & Barrantes-Vidal, N. (2015). Attachment style predicts affect, cognitive appraisals, and social functioning in daily life. Frontiers in psychology, 6, 296. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00296 types of attachment styles include:

- Secure attachment, wherein individuals feel comfortable with emotional intimacy and seek support from others when needed

- Anxious-preoccupied attachment, wherein individuals tend to worry about abandonment and seek constant reassurance and validation from their partners

- Dismissive-avoidant attachment, wherein individuals tend to avoid emotional intimacy and view relationships as less important than independence

- Fearful-avoidant attachment, wherein individuals tend to have conflicting desires for intimacy and independence, often feeling overwhelmed by emotional closeness

Stages Of Attachment

Research 6 Rees C. (2007). Childhood attachment. The British journal of general practice : the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 57(544), 920–922. https://doi.org/10.3399/096016407782317955 attributes the common stages of attachment and the development of attachment patterns to the following:

1. Pre-attachment (Birth To 6 Weeks)

Infants develop the ability to recognize their caregivers and become attached through instinctual behaviors such as crying and grasping.

2. Attachment In The Making (6 Weeks To 6-8 Months)

Infants develop a sense of trust and rely on their caregivers to meet their needs. A secure childhood attachment style may develop during this stage.

3. Clear-cut Attachment (6-8 Months To 18-24 Months)

Infants become more independent but still rely on their caregivers for emotional support and exploration. Attachment styles such as anxious-preoccupied, dismissive-avoidant, and secure may emerge during this stage.

4. Formation Of Reciprocal Relationships (18-24 Months And Beyond)

Children become more independent and start to form relationships outside of the primary caregiver. Attachment patterns may continue to develop or change during this stage, influenced by experiences with caregivers and relationships with peers.

5. Attachment Patterns In Adolescence And Adulthood

Attachment patterns established in childhood may continue into adolescence and adulthood, but can also be influenced by new experiences and relationships. These include romantic relationships, friendships, and personal attachments formed at the workplace.

Attachment And Mental Health

Patterns of attachment and mental health are intricately related. The quality of attachment that an individual forms with their caregiver can have a significant impact on his/her mental health and well-being throughout life.

Positive attachment patterns (such as secure attachment 7 Hong, Y. R., & Park, J. S. (2012). Impact of attachment, temperament and parenting on human development. Korean journal of pediatrics, 55(12), 449–454. https://doi.org/10.3345/kjp.2012.55.12.449 ) can provide a sense of safety, security, and support, which can lead to positive mental health outcomes. Individuals with secure attachment styles tend to have better self-esteem, more positive self-concepts and are less likely to develop mental health problems.

Read More About Self-Esteem Here

Contrarily, negative attachment patterns 8 Simpson, J. A., & Steven Rholes, W. (2017). Adult Attachment, Stress, and Romantic Relationships. Current opinion in psychology, 13, 19–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.04.006 (such as anxious-preoccupied, dismissive-avoidant, or fearful-avoidant attachment) are associated with poor self-esteem, low self-worth, and problematic behavior marked by jealousy, manipulation, possessiveness, etc. Such attachment patterns can also enhance vulnerability for developing mental health conditions like:

- Depression

- Anxiety

- Post-traumatic stress disorder

- Psychotic Disorder

- Substance use disorder

- Personality disorder, etc.

Read More About Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Here

What Are Attachment Issues?

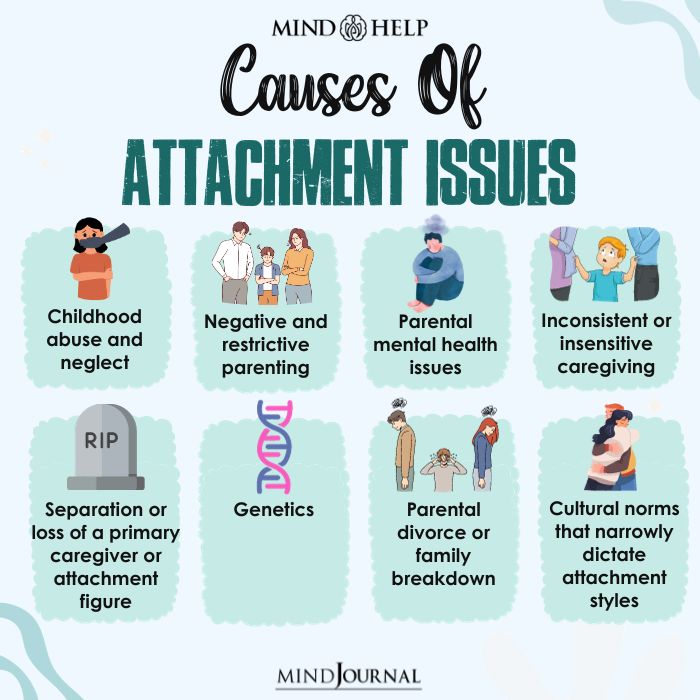

Attachment issues refer to difficulties in forming and maintaining healthy attachments 9 Turner, M., Beckwith, H., Duschinsky, R., Forslund, T., Foster, S. L., Coughlan, B., Pal, S., & Schuengel, C. (2019). Attachment difficulties and disorders. InnovAiT, 12(4), 173. https://doi.org/10.1177/1755738018823817 or relationships with others. Individuals with childhood attachment issues may struggle with trust, intimacy, and emotional regulation in their relationships.

These issues can arise from a variety of factors such as early childhood experiences of neglect, abuse, or separation from caregivers, as well as from other traumatic life experiences.

Signs Of Attachment Issues

Common signs of attachment issues and/or attachment disorders 10 Hornor G. (2019). Attachment Disorders. Journal of pediatric health care : official publication of National Association of Pediatric Nurse Associates & Practitioners, 33(5), 612–622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2019.04.017 include:

- Difficulty forming close relationships

- Fear of rejection or abandonment

- Lack of trust in others

- Emotional detachment

- Impulsivity

- Inability to seek comfort or help from others

- A lack of interest in social interactions

How To Get Rid Of Attachment Issues

Treatment 11 Health (UK), N. C. C. for M. (2015). Identification and assessment of attachment difficulties. In www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK356191/ for chronic attachment issues or attachment disorders may involve therapy to address any underlying trauma or negative attachment experiences.

Therapists may use various approaches (such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, play therapy, attachment-based therapy, theraplay, emotionally focused therapy dialectical behavior therapy, and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing) to help individuals develop healthy attachment styles, build trust in others, and learn to regulate their emotions. In some cases, medication may also be prescribed to manage associated symptoms of anxiety or depression.

How To Develop A Secure Attachment Style In Children

In children, attachment issues may manifest as developmental delays, inability to seek comfort from caregivers, or lack of interest in social interactions. It can be challenging for them and their caregivers to address these difficulties, but, aside from seeking medical help, developing healthy self-help coping strategies 12 Hong, Y. R., & Park, J. S. (2012). Impact of attachment, temperament and parenting on human development. Korean journal of pediatrics, 55(12), 449–454. https://doi.org/10.3345/kjp.2012.55.12.449 can help to develop secure attachment styles in children.

- Be consistent and responsive in caregiving.

- Use physical touch to promote feelings of security.

- Communicate openly and respond promptly and sensitively to the child’s needs.

- Foster positive interactions through play and communication.

- Offer opportunities for secure attachments with others like relatives, friends, etc.

- Use positive reinforcement for good behavior (like hugs or other affectionate gestures as rewards for tasks done)

- Provide a safe and predictable environment.

- Seek professional help if needed.

- Maintain consistency during stress or change.

How To Develop A Secure Attachment Style As An Adult

If you are someone suffering from attachment issues, consider the following tips 13 Mikulincer, M., & R Shaver, P. (2020). Enhancing the “Broaden and Build” Cycle of Attachment Security in Adulthood: From the Laboratory to Relational Contexts and Societal Systems. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(6), 2054. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17062054 to manage your unhealthy attachment style:

- Practice self-awareness and identify attachment patterns.

- Seek professional help to address past attachment wounds.

- Engage in open and honest communication with partners.

- Build emotional intimacy through vulnerability and trust.

- Practice active listening and empathetic responses.

- Set healthy boundaries and respect each other’s autonomy.

- Practice forgiveness and repair in times of conflict.

- Prioritize emotional and physical safety in relationships.

- Engage in activities that promote emotional regulation and self-care.

- Continuously work on developing and maintaining healthy attachment styles.

Takeaway

Childhood attachment is a crucial coping mechanism for infants as it helps them form a mental representation of their caregiver, which enables them to explore the world without becoming distressed.

Therefore, it is vital for parents to provide a nurturing environment that fosters secure attachment to promote healthy development and ensure their child grows up to become a responsible and emotionally stable adult.

At a Glance

- Attachment refers to the emotional bond that develops between individuals, especially between a child and their primary caregiver.

- Attachment patterns can influence the way individuals interact with others throughout their lives.

- Attachment theory is a psychological framework that explains how the emotional bonds between individuals can shape their social and emotional development.

- There are various types of attachment styles, including secure, anxious-preoccupied, dismissive-avoidant, and fearful-avoidant attachment.

- Attachment patterns can be established in childhood and may continue into adolescence and adulthood, influencing mental health outcomes.

- Attachment issues occur when an individual struggles to form healthy attachments or bonds with others due to a history of neglect, abuse, or inconsistent care during childhood.

- Treatment for attachment disorder may involve therapy and medication.

- Developing healthy self-help coping strategies can help to develop secure attachment styles in children and adults.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why do we need to form attachments?

We need to form attachments as humans are social beings and crave connections with others.

2. What is the most important factor in attachment?

The most important factor in attachment is the quality of caregiving, especially in early childhood.

3. What can interfere with our attachment style?

Interference with attachment style can occur due to factors such as childhood trauma, inconsistent caregiving, or environmental stressors.

4. What happens if an attachment is not formed?

If an attachment is not formed, it can lead to a range of negative outcomes including social and emotional difficulties, behavioral problems, and mental health issues.