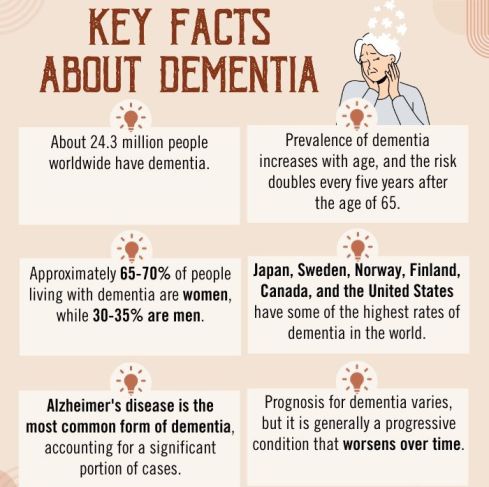

Dementia, a progressive neurological disorder, not only affects cognitive functions but also exerts a profound influence on mental health. Individuals coping with dementia often grapple with emotional distress, mood swings, and behavioral changes, making it essential to understand the intricate connection between dementia and mental well-being for better care and support.

What Is Dementia?

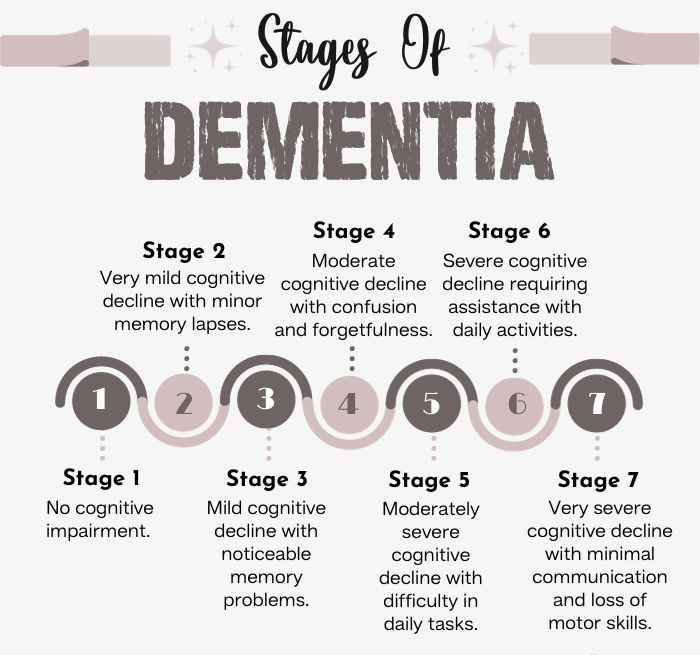

Dementia is a complex and progressive neurological disorder characterized by a decline in cognitive abilities 1 Emmady, P. D., & Tadi, P. (2022). Dementia. PubMed; StatPearls Publishing. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557444/#:~:text=Dementia%20describes%20an%20overall%20decline , memory, reasoning, and other intellectual functions that interfere with an individual’s daily life and functioning. The onset of the symptoms of dementia is usually gradual and worsens over time, ultimately leading to significant impairment in a person’s ability to perform everyday activities independently.

Dementia is not a specific disease but rather an umbrella term encompassing a range of conditions that share similar symptoms. The common nature of the different types of dementia involves the degeneration of brain cells, particularly neurons, which leads to the disruption of communication between different parts of the brain.

In the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), dementia is categorized 2 Cunningham, E. L., McGuinness, B., Herron, B., & Passmore, A. P. (2015). Dementia. The Ulster medical journal, 84(2), 79–87. under the broader term “neurocognitive disorders.” This classification reflects a shift in focus from just cognitive impairment to the underlying neurological changes that contribute to cognitive decline in the various types of dementia.

Read More About Memory Here

Symptoms Of Dementia

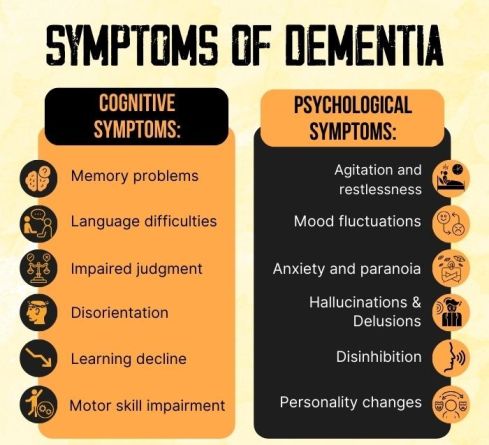

The common symptoms of dementia include 3 Arvanitakis, Z., & Bennett, D. A. (2019). What Is Dementia?. JAMA, 322(17), 1728. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.11653 :

- Memory problems: Repetitive questions or forgetting familiar faces.

- Language difficulties: Trouble finding words, understanding speech.

- Impaired judgment: Challenges in decision-making and problem-solving.

- Disorientation: Confusion about time, place, and surroundings.

- Learning decline: Struggles with acquiring new skills and adapting.

- Motor skill impairment: Coordination and daily tasks are affected.

- Agitation and restlessness.

- Mood fluctuations: Shifts between depression, sadness, and apathy.

- Anxiety and paranoia: Unsettling feelings and baseless suspicions.

- Hallucinations: Hearing voices, seeing nonexistent things.

- Delusions: Holding false beliefs, often about theft or infidelity.

- Disinhibition: Impulsive and socially inappropriate behavior.

- Personality changes: Shifts in behavior and attitudes.

Read More About Paranoia Here

Types Of Dementia

The different types of dementia include 4 Cloak, N., & Al Khalili, Y. (2020). Behavioral And Psychological Symptoms In Dementia (BPSD). PubMed; StatPearls Publishing. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551552/ :

- Alzheimer’s Disease: Progressive memory loss and cognitive decline due to abnormal brain proteins.

- Vascular Dementia: Cognitive impairment from reduced brain blood flow, often due to strokes.

- Lewy Body Dementia: Fluctuating cognition, visual hallucinations, and motor issues due to Lewy body proteins.

- Frontotemporal Dementia: Behavior, personality, and language changes from frontal and temporal lobe damage.

- Mixed Dementia: Overlapping symptoms of various types, like Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia.

- Parkinson’s Disease Dementia: Cognitive decline alongside Parkinson’s motor symptoms.

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease: Rapid cognitive decline caused by abnormal brain prion proteins.

- Huntington’s Disease: Genetic disorder leading to motor problems, behavioral changes, and cognitive deterioration.

- Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome: Memory problems and confusion due to thiamine deficiency, often from alcohol misuse.

- Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus: Gait issues, cognitive decline, and urinary problems from excess brain fluid.

Causes Of Dementia

The common 5 Emmady, P. D., & Tadi, P. (2020). Dementia. PubMed; StatPearls Publishing. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32491376/ causes for the various types of dementia include:

- Vascular factors like hypertension, atherosclerosis, and strokes

- Protein buildup in damaged frontal and temporal lobes

- Abnormal triggers of prion proteins

- Chronic alcohol-related vitamin B1 deficiency.

- Neurological disorders like Parkinson’s, multiple sclerosis, and HIV/AIDS

- Traumatic brain injury

- Brain-affecting infections like encephalitis

- Metabolic disorders like hypothyroidism

- Long-term contact with chemicals or heavy metals

- Lewy body accumulation in certain brain regions

How Does Dementia Affect Mental Health?

The different types of dementia affect mental health in a number of ways 6 Scott, K. R., & Barrett, A. M. (2007). Dementia syndromes: evaluation and treatment. Expert review of neurotherapeutics, 7(4), 407–422. https://doi.org/10.1586/14737175.7.4.407 :

- Cognitive Decline: Dementia causes progressive mental deterioration, affecting memory and thinking.

- Emotional Strain: Dementia often leads to mood swings, anxiety, and depression due to cognitive decline.

- Personality Shifts: It can alter a person’s personality and behavior, making them harder to recognize.

- Caregiver Stress: Caregivers may experience high stress levels due to the demands of caring for someone with dementia.

- Social Isolation: Dementia can lead to social withdrawal due to communication difficulties.

- Loss Of Independence: It gradually erodes a person’s ability to live independently, impacting self-esteem.

- Psychiatric Symptoms: Some forms of dementia may cause hallucinations, delusions, and paranoia.

- Coping Challenges: People with dementia may struggle to handle daily tasks, leading to frustration.

- Reduced Quality Of Life: Overall, dementia significantly lowers the quality of life for both patients and caregivers, affecting mental well-being.

Read More About Depression Here

Diagnosis Of Dementia

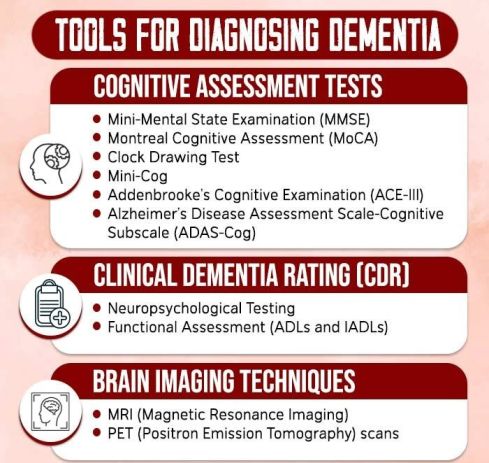

Diagnosis of dementia, as per DSM-5 criteria 7 Salvadori, E., Poggesi, A., Pracucci, G., Chiti, A., Ciolli, L., Cosottini, M., Del Bene, A., De Stefano, N., Diciotti, S., Di Donato, I., Ginestroni, A., Marini, S., Mascalchi, M., Nannucci, S., Orlandi, G., Pasi, M., Pescini, F., Valenti, R., Federico, A., Dotti, M. T., … VMCI-Tuscany Study Group (2018). Application of the DSM-5 Criteria for Major Neurocognitive Disorder to Vascular MCI Patients. Dementia and geriatric cognitive disorders extra, 8(1), 104–116. https://doi.org/10.1159/000487130 , involves assessing significant cognitive decline affecting daily life, ruling out other potential causes, and considering functional impairment that accompany the early signs of dementia.

The process 8 Arvanitakis, Z., Shah, R. C., & Bennett, D. A. (2019). Diagnosis and Management of Dementia: Review. JAMA, 322(16), 1589–1599. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.4782 includes clinical evaluation, cognitive testing 9 Arevalo-Rodriguez, I., Smailagic, N., Roqué I Figuls, M., Ciapponi, A., Sanchez-Perez, E., Giannakou, A., Pedraza, O. L., Bonfill Cosp, X., & Cullum, S. (2015). Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for the detection of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 2015(3), CD010783. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010783.pub2 , neuroimaging, lab tests, functional assessments, psychiatric evaluation, caregiver input, and periodic follow-ups. A qualified healthcare professional should make the diagnosis, which is essential for accessing appropriate care and support, managing the condition, and planning for the future.

Read More About Cognitive Decline Here

Treatment For Dementia

There is no cure for most types of dementia, but various therapies and medications can be used to address the early signs of dementia and slow down the progression of the disease. The methods 10 Perneczky R. (2019). Dementia treatment versus prevention. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 21(1), 43–51. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2019.21.1/rperneczky in the treatment for dementia include:

1. Medications:

Cholinesterase inhibitors 11 Grossberg G. T. (2003). Cholinesterase inhibitors for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease:: getting on and staying on. Current therapeutic research, clinical and experimental, 64(4), 216–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0011-393X(03)00059-6 like donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine are frequently prescribed for Alzheimer’s disease to enhance cognitive function and provide temporary relief from symptoms. On the other hand, memantine, an NMDA receptor antagonist 12 Kuns, B., Rosani, A., & Varghese, D. (2022, July 11). Memantine. PubMed; StatPearls Publishing. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK500025/ , is utilized for moderate to severe Alzheimer’s to regulate the neurotransmitter glutamate, potentially slowing down the disease’s progression.

2. Cognitive Stimulation Therapy:

Structured programs or activities that engage individuals in mental exercises, reminiscence therapy, and social interaction 13 Sukhawathanakul, P., Crizzle, A., Tuokko, H., Naglie, G., & Rapoport, M. J. (2021). Psychotherapeutic Interventions for Dementia: a Systematic Review. Canadian geriatrics journal : CGJ, 24(3), 222–236. https://doi.org/10.5770/cgj.24.447 . These therapies can help maintain cognitive function and improve well-being.

3. Occupational Therapy:

Occupational therapists help individuals with dementia maintain their independence in daily activities by providing strategies and adaptive techniques (like memory aids, mealtime assistance, memory books, etc.).

5. Speech And Language Therapy:

Speech therapists assist with communication difficulties, language problems, and swallowing issues that can occur in dementia.

6. Behavioral Management:

Techniques like behavioral therapy, behavior modification, and environmental modifications can help manage challenging behaviors associated with dementia, such as agitation and aggression.

7. Music And Art Therapy:

These therapies can provide emotional and psychological benefits, improving mood and reducing anxiety in individuals with dementia.

Read More About Art Therapy Here

How Do You Help Someone With Dementia?

Consider the following measures 14 Rakesh, G., Szabo, S. T., Alexopoulos, G. S., & Zannas, A. S. (2017). Strategies for dementia prevention: latest evidence and implications. Therapeutic advances in chronic disease, 8(8-9), 121–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/2040622317712442 on how to help someone with dementia:

- Learn About Dementia: Educate yourself on their specific type of dementia.

- Create Routine: Establish a structured daily schedule.

- Simple Communication: Use clear, simple language and non-verbal cues.

- Be Patient: Allow extra time for tasks and conversations.

- Ensure Safety: Remove hazards and secure the environment.

- Assist With Daily Tasks: Help with bathing, dressing, and eating.

- Promote Independence: Encourage self-care when possible.

- Engage In Activities: Enjoy hobbies and activities together.

- Offer Choices: Give options to empower decision-making.

- Stay Calm: Remain composed during challenging moments.

- Nutrition And Hydration: Ensure a balanced diet and hydration.

- Manage Medications: Administer prescribed medications.

- Health Checkups: Attend medical appointments regularly.

- Respite Care: Seek short breaks for caregivers.

- Support Groups: Connect with caregiver support networks.

- Legal And Financial Planning: Assist with legal and financial matters.

- Monitor Changes: Be vigilant for behavioral or health changes.

- Flexibility: Adapt to evolving needs and abilities.

- Affection: Express love through touch and kind words.

- Professional Help: Consider counseling and therapy support.

- Future Planning: Discuss long-term care and end-of-life preferences.

Read More About Decision-Making Here

Coping With Dementia

Consider the following strategies 15 Robinson, L., Tang, E., & Taylor, J. P. (2015). Dementia: timely diagnosis and early intervention. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 350, h3029. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h3029 for coping with dementia:

- Educate Yourself: Learn about dementia’s progression.

- Stay Patient: Remain calm during challenging moments.

- Maintain Routine: Establish a structured daily schedule.

- Effective Communication: Use simple language and non-verbal cues.

- Safety Measures: Create a safe living environment.

- Engage In Activities: Enjoy hobbies and engage in reminiscence-based tricks (like mnemonics) together.

- Support Network: Connect with caregiver support groups.

- Legal And Financial Planning: Address legal and financial matters.

- Health Monitoring: Attend regular medical checkups.

- Respite Care: Consider short breaks for caregivers.

Takeaway

Dementia is a complex and challenging condition that affects millions of individuals and their families worldwide. While there is no cure, advances in research and a better understanding of the symptoms of dementia have led to improved care and support for those living with the condition.

Empathy, education, and a patient-centered approach are key in providing the best possible quality of life for individuals coping with dementia. With ongoing research and a commitment to compassionate care, there is hope for a brighter future in the treatment for dementia.

At A Glance

- Dementia is a progressive neurological disorder characterized by cognitive decline, memory loss, and behavioral changes.

- The various types of dementia include Alzheimer’s, vascular, Lewy body, and frontotemporal dementia, each with distinct symptoms and causes.

- The causes of dementia include brain injury, exposure to toxins, etc.

- Dementia affects mental health, leading to mood fluctuations, anxiety, and hallucinations, among other challenges.

- Diagnosis of dementia involves assessing cognitive decline and functional impairment.

- Treatment for dementia focuses on the management of the symptoms of dementia using medications and therapies.

- To help someone with dementia, caregivers should create a routine, communicate effectively, ensure safety, engage in activities, and seek support.

- Coping with dementia involves education, patience, routine maintenance, and addressing legal and financial matters.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the early signs of dementia?

Early signs of dementia may include memory problems, difficulty finding words, impaired judgment, and mood fluctuations.

2. Is dementia reversible?

The symptoms of dementia are generally not reversible, although some cases may be caused by treatable conditions like vitamin deficiencies or medication side effects.

3. What are the questions not to ask a person with dementia?

Avoid asking a person coping with dementia questions that may cause confusion or distress, such as complex or abstract questions, or questions about distant past events.

4. How does dementia affect mental health?

The major types of dementia can significantly impact mental health by causing memory loss, confusion, mood swings, and behavioral changes, leading to emotional distress and anxiety.

5. How do you help someone with dementia?

To help someone coping with dementia, provide a structured and familiar environment, offer emotional support and patience, and engage in meaningful activities. Consider professional care and resources in the diagnosis of dementia.