Performance anxiety is a type of anxiety that can affect individuals of all ages and backgrounds. This type of anxiety can be so severe that it can significantly impact an individual’s ability to perform well or even participate in an activity, and can have a negative impact on their personal and professional lives.

What is Performance Anxiety?

Performance anxiety is characterized by intense fear, worry, and nervousness surrounding the performance of a specific task or activity, such as public speaking, musical performances, athletic competitions, and artistic performances. People may also experience physical symptoms such as sweating, shaking, nausea, or an increased heart rate, which can further exacerbate anxiety.

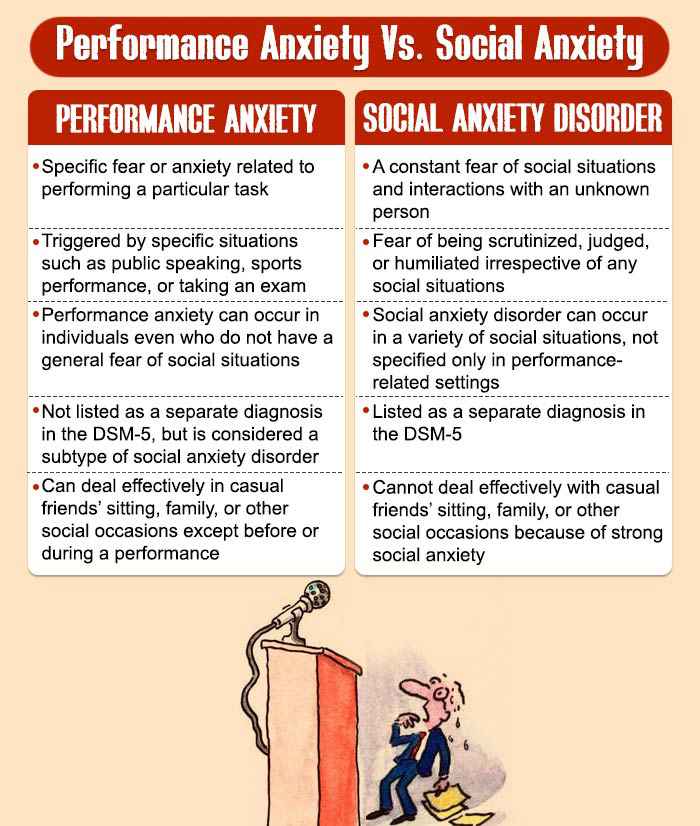

Performance anxiety is a common experience, with up to 30% 1 Tejwani, V., Ha, D., & Isada, C. (2016). Observations: Public Speaking Anxiety in Graduate Medical Education–A Matter of Interpersonal and Communication Skills?. Journal of graduate medical education, 8(1), 111. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-15-00500.1 of individuals experiencing fear when speaking in public. While not explicitly listed as a diagnosis in the DSM-5 2 Rose, G. M., & Tadi, P. (2020). Social Anxiety Disorder. PubMed; StatPearls Publishing. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK555890/ , performance anxiety is considered a subtype of social anxiety disorder, which is included in the manual, which signifies that the symptoms and criteria for social anxiety disorder can also be applicable to performance anxiety as well.

Certain factors may increase an individual’s susceptibility 3 Takac, M., Collett, J., Blom, K. J., Conduit, R., Rehm, I., & De Foe, A. (2019). Public speaking anxiety decreases within repeated virtual reality training sessions. PloS one, 14(5), e0216288. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216288 to performance anxiety. For example, past negative experiences, a high level of self-doubt, or a history of anxiety disorder or other mental health conditions can all contribute to the development of performance anxiety.

Read More About Anxiety Here

Signs of Performance Anxiety

Here are some basic signs that may be observed in performance anxiety

Performance anxiety in children:

- Extreme shyness 4 Jefferson J. W. (2001). Social Anxiety Disorder: More Than Just a Little Shyness. Primary care companion to the Journal of clinical psychiatry, 3(1), 4–9. https://doi.org/10.4088/pcc.v03n0102 or clinginess.

- Fear or avoidance of participating in school or extracurricular activities.

- Excessive worry about 5 Hildebrandt, H., Nübling, M., & Candia, V. (2012). Increment of fatigue, depression, and stage fright during the first year of high-level education in music students. Medical problems of performing artists, 27(1), 43–48. making mistakes or failing.

- Physical symptoms such as stomachaches, headaches, or nausea 6 Kumar, R., Asif, S., Bali, A., Dang, A. K., & Gonzalez, D. A. (2022). The Development and Impact of Anxiety With Migraines: A Narrative Review. Cureus, 14(6), e26419. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.26419 before a performance.

- Crying, tantrums, or pleading not to participate 7 National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health UK. (2013). SOCIAL ANXIETY DISORDER. Nih.gov; British Psychological Society. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK327674/ .

- Inability to concentrate or remember lines 8 Nagel J. J. (2018). Memory Slip: Stage Fright and Performing Musicians. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 66(4), 679–700. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003065118795432 or choreography.

Performance anxiety in adults:

- Extreme nervousness or fear before or during a performance.

- Physical symptoms such as sweating 9 de Groot, J. H. B., Kirk, P. A., & Gottfried, J. A. (2020). Encoding fear intensity in human sweat. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 375(1800), 20190271. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0271 , shaking, or rapid heartbeat.

- Avoidance of performance situations or procrastination 10 Desai, M., Pandit, U., Nerurkar, A., Verma, C., & Gandhi, S. (2021). Test anxiety and procrastination in physiotherapy students. Journal of education and health promotion, 10, 132. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_851_20 .

- Negative self-talk or self-doubt 11 Ankori, G., Tzabari, D., Hager, T., & Golan, M. (2022). From Self-Doubt to Pride: Understanding the Empowering Effects of Delivering School-Based Wellness Programmes for Emerging Adult Facilitators-A Qualitative Study. International journal of environmental research and public health, 19(14), 8421. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148421 .

- Difficulty concentrating or remembering lines or choreography.

- Self-medicating with drugs or alcohol 12 Sinha R. (2008). Chronic stress, drug use, and vulnerability to addiction. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1141, 105–130. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1441.030 before a performance.

Types of Performance Anxiety

Here are some types 13 Rowland, D. L., & van Lankveld, J. J. D. M. (2019). Anxiety and Performance in Sex, Sport, and Stage: Identifying Common Ground. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 1615. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01615 of performance anxiety that may occur in both adults and children:

1. Public Speaking Anxiety

This is the most common type of performance anxiety and refers to the fear of speaking or presenting in front of an audience. This can occur in both adults and children and may be triggered by various factors such as fear of embarrassment or failure.

2. Test-taking Anxiety

Test-taking anxiety is a type of performance anxiety that is triggered by the prospect of taking an exam 14 Hanfesa, S., Tilahun, T., Dessie, N., Shumet, S., & Salelew, E. (2020). Test Anxiety and Associated Factors Among First-Year Health Science Students of University of Gondar, Northwest Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Advances in medical education and practice, 11, 817–824. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S275490 . This can result in symptoms such as sweating, rapid heartbeat, and difficulty concentrating.

3. Performance Anxiety in Sports

This type of performance anxiety is common among athletes and refers to the fear of performing poorly 15 Ford, J. L., Ildefonso, K., Jones, M. L., & Arvinen-Barrow, M. (2017). Sport-related anxiety: current insights. Open access journal of sports medicine, 8, 205–212. https://doi.org/10.2147/OAJSM.S125845 in a game or competition. This can result in symptoms such as shaking, nausea, and tension.

4. Musical Performance Anxiety

Musicians, both amateur and professional, may experience performance anxiety when playing/singing in front of an audience. This can result in performance anxiety symptoms 16 Guyon, A. J. A. A., Studer, R. K., Hildebrandt, H., Horsch, A., Nater, U. M., & Gomez, P. (2020). Music performance anxiety from the challenge and threat perspective: psychophysiological and performance outcomes. BMC psychology, 8(1), 87. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-020-00448-8 such as trembling, sweating, and forgetfulness.

Causes of Performance Anxiety

Performance anxiety in children can be caused by a variety of factors 17 Beesdo, K., Knappe, S., & Pine, D. S. (2009). Anxiety and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: developmental issues and implications for DSM-V. The Psychiatric clinics of North America, 32(3), 483–524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2009.06.002 , including:

1. Lack of Experience

Children who have not had experience performing in front of others may feel unsure about how to behave, what the audience’s reaction will be, or to what extent they will be judged–these make children anxious during their performance.

2. Fear of Failure

Children who have a fear of failure 18 Steimer T. (2002). The biology of fear- and anxiety-related behaviors. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 4(3), 231–249. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2002.4.3/tsteimer may become anxious about performing, as they may feel the pressure that they will not be able to perform well enough and will disappoint their parents or teachers.

3. Bullying or Teasing

Children who have been bullied 19 Rivara, F., & Le Menestrel, S. (2016, September 14). Consequences of Bullying Behavior. Nih.gov; National Academies Press (US). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK390414/ or teased by peers may become anxious about performing in front of others, as they worry about being judged or ridiculed.

Read More About Bullying Here

4. Genetics

There may be a genetic component 20 Meier, S. M., & Deckert, J. (2019). Genetics of Anxiety Disorders. Current psychiatry reports, 21(3), 16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-1002-7 to performance anxiety, as some children may be more prone to anxiety than others due to their genes.

Read More About Genetics Here

5. Negative Self-talk

Negative self-talk 21 Kim, J., Kwon, J. H., Kim, J., Kim, E. J., Kim, H. E., Kyeong, S., & Kim, J. J. (2021). The effects of positive or negative self-talk on the alteration of brain functional connectivity by performing cognitive tasks. Scientific reports, 11(1), 14873. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-94328-9 in children can lead to anxiety and self-doubt, causing them to feel incapable or unworthy of success. This can result in a lack of confidence and avoidance of certain tasks or situations.

Common causes of performance anxiety in adults include:

1. Negative Past Experiences

Adults who have had negative experiences 22 McQuaid, A., Sanatinia, R., Farquharson, L., Shah, P., Quirk, A., Baldwin, D. S., & Crawford, M. (2021). Patient experience of lasting negative effects of psychological interventions for anxiety and depression in secondary mental health care services: a national cross-sectional study. BMC psychiatry, 21(1), 578. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03588-2 in similar situations, such as failing or being judged or criticized, may become anxious about similar future performances.

2. High Expectations and Perfectionism

Adults who may have high expectations 23 Lamarca, G. A., Vettore, M. V., & Monteiro da Silva, A. M. (2018). The Influence of Stress and Anxiety on the Expectation, Perception and Memory of Dental Pain in Schoolchildren. Dentistry journal, 6(4), 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj6040060 for themselves and a strong need to be perfect can make them worry about making mistakes or not meeting their high standards.

Read More About Perfectionism Here

3. Lack of Confidence

Adults who lack confidence in their abilities 24 Nguyen, D. T., Wright, E. P., Dedding, C., Pham, T. T., & Bunders, J. (2019). Low Self-Esteem and Its Association With Anxiety, Depression, and Suicidal Ideation in Vietnamese Secondary School Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Frontiers in psychiatry, 10, 698. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00698 may become anxious about their performance, as they worry about not being able to perform well.

4. Stressful Life Events

Adults who are going through stressful life events 25 Daviu, N., Bruchas, M. R., Moghaddam, B., Sandi, C., & Beyeler, A. (2019). Neurobiological links between stress and anxiety. Neurobiology of stress, 11, 100191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ynstr.2019.100191 , such as a divorce or job loss, may become anxious about their performance as a result of the stress.

5. Physical and Mental Health Symptoms

Mental health conditions such as depression 26 Mirzaei, M., Yasini Ardekani, S. M., Mirzaei, M., & Dehghani, A. (2019). Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety and Stress among Adult Population: Results of Yazd Health Study. Iranian journal of psychiatry, 14(2), 137–146. can lead to feelings of hopelessness and low self-esteem, while anxiety can cause physical symptoms like sweating and trembling, which altogether can distract and affect an individual’s performance level.

Diagnosing Performance Anxiety

When it comes to diagnosing performance anxiety, there are several tools and steps 27 Grupe, D. W., & Nitschke, J. B. (2013). Uncertainty and anticipation in anxiety: an integrated neurobiological and psychological perspective. Nature reviews. Neuroscience, 14(7), 488–501. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3524 that a mental health professional may use:

1. Clinical Interview

The first step is a clinical interview, where the professional may ask questions about symptoms 28 Dalrymple, K. L., & Zimmerman, M. (2008). Screening for social fears and social anxiety disorder in psychiatric outpatients. Comprehensive psychiatry, 49(4), 399–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.01.009 , medical history, and personal background.

2. Observation

The mental health professional may also observe an individual 29 Mian, N. D., Carter, A. S., Pine, D. S., Wakschlag, L. S., & Briggs-Gowan, M. J. (2015). Development of a novel observational measure for anxiety in young children: The Anxiety Dimensional Observation Scale. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines, 56(9), 1017–1025. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12407 during a performance to assess his/her anxiety level and other symptoms.

3. Physical Exams

In some cases, a medical examination 30 Hashmat, S., Hashmat, M., Amanullah, F., & Aziz, S. (2008). Factors causing exam anxiety in medical students. JPMA. The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association, 58(4), 167–170. may be necessary to rule out any underlying medical conditions that may be contributing to the symptoms of performance anxiety.

4. Psychological Assessments

A mental health professional may also use standardized psychological assessments 31 Rose, M., & Devine, J. (2014). Assessment of patient-reported symptoms of anxiety. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 16(2), 197–211. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2014.16.2/mrose to help diagnose performance anxiety. These assessments can include:

- State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI 32 Julian L. J. (2011). Measures of anxiety: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety (HADS-A). Arthritis care & research, 63 Suppl 11(0 11), S467–S472. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.20561 )

- Performance Anxiety Inventory (API 33 Schmidt, N. B., Keough, M. E., Timpano, K. R., & Richey, J. A. (2008). Anxiety sensitivity profile: predictive and incremental validity. Journal of anxiety disorders, 22(7), 1180–1189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.12.003 )

- Test Anxiety Inventory (TAI 34 Taylor, J., & Deane, F. P. (2002). Development of a short form of the Test Anxiety Inventory (TAI). The Journal of general psychology, 129(2), 127–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221300209603133 )

- Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS 35 Caballo, V. E., Salazar, I. C., Arias, V., Hofmann, S. G., & Curtiss, J. (2019). Psychometric properties of the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale in a large cross-cultural Spanish and Portuguese speaking sample. Revista brasileira de psiquiatria (Sao Paulo, Brazil : 1999), 41(2), 122–130. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2018-0006 )

Treating Performance Anxiety

Here are some common treatment options 36 Clark, D. B., & Agras, W. S. (1991). The assessment and treatment of performance anxiety in musicians. The American journal of psychiatry, 148(5), 598–605. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.148.5.598 for both children and adults with performance anxiety:

1. Cognitive-behavioral Therapy (CBT)

CBT is a type of therapy that helps individuals identify and change negative thoughts and beliefs that contribute to anxiety 37 Kaczkurkin, A. N., & Foa, E. B. (2015). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders: an update on the empirical evidence. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 17(3), 337–346. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2015.17.3/akaczkurkin . It can be effective in treating performance anxiety by helping individuals develop coping skills and strategies for managing their symptoms during performances.

Read More About Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) Here

2. Mindfulness-based Interventions

Mindfulness-based interventions such as meditation and yoga 38 Ebrahiminejad, S., Poursharifi, H., Bakhshiour Roodsari, A., Zeinodini, Z., & Noorbakhsh, S. (2016). The Effectiveness of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy on Iranian Female Adolescents Suffering From Social Anxiety. Iranian Red Crescent medical journal, 18(11), e25116. https://doi.org/10.5812/ircmj.25116 can help individuals develop greater awareness and acceptance of their thoughts and emotions, which can reduce anxiety and improve performance.

Read More About Mindfulness Here

3. Relaxation Techniques

Relaxation techniques, such as deep breathing, muscle relaxation 39 Rowland, D. L., Moyle, G., & Cooper, S. E. (2021). Remediation Strategies for Performance Anxiety across Sex, Sport and Stage: Identifying Common Approaches and a Unified Cognitive Model. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(19), 10160. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910160 , and visualization, can be effective in reducing symptoms of anxiety before and during performances.

4. Medication

Beta-blockers, benzodiazepines, and antidepressants, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are medications 40 Garakani, A., Murrough, J. W., Freire, R. C., Thom, R. P., Larkin, K., Buono, F. D., & Iosifescu, D. V. (2020). Pharmacotherapy of Anxiety Disorders: Current and Emerging Treatment Options. Frontiers in psychiatry, 11, 595584. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.595584 that may be used to treat performance anxiety. They can help regulate mood and reduce symptoms of anxiety that contribute to their performance output.

Tips to Overcome Performance Anxiety

Several strategies 41 Powell D. H. (2004). Treating individuals with debilitating performance anxiety: An introduction. Journal of clinical psychology, 60(8), 801–808. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20038 can help individuals overcome performance anxiety, including:

1. Identify and Challenge Negative Thoughts

It can be helpful to identify and challenge these negative thoughts by asking yourself if they are realistic or if there is evidence to support them.

2. Gradual Exposure

Gradually expose yourself 42 McGuire, J. F., Lewin, A. B., & Storch, E. A. (2014). Enhancing exposure therapy for anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder. Expert review of neurotherapeutics, 14(8), 893–910. https://doi.org/10.1586/14737175.2014.934677 to the situation that triggers your anxiety. Start with a less anxiety-provoking situation and work up to the more challenging ones. This can help desensitize you to the situation and reduce anxiety over time.

3. Positive Self-talk

Use positive self-talk 43 Walter, N., Nikoleizig, L., & Alfermann, D. (2019). Effects of Self-Talk Training on Competitive Anxiety, Self-Efficacy, Volitional Skills, and Performance: An Intervention Study with Junior Sub-Elite Athletes. Sports (Basel, Switzerland), 7(6), 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports7060148 to reinforce a positive attitude and belief in your abilities. Focus on your strengths and past successes rather than dwelling on potential failures.

4. Coaching and Rehearsal

Working with a coach or rehearsing a performance 44 Halvari H. (1996). Effects of mental practice on performance are moderated by cognitive anxiety as measured by the Sport Competition Anxiety Test. Perceptual and motor skills, 83(3 Pt 2), 1375–1383. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1996.83.3f.1375 can help you to build confidence and reduce anxiety. The coach can provide feedback and support to help you feel more prepared and confident in your performance.

5. Practice Self-care

Take care of yourself both physically and emotionally. Make time for activities that you enjoy, such as exercise 45 Anderson, E., & Shivakumar, G. (2013). Effects of exercise and physical activity on anxiety. Frontiers in psychiatry, 4, 27. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00027 , reading, or spending time with loved ones.

6. Seek Support

Seek support 46 Heinig, I., Wittchen, H. U., & Knappe, S. (2021). Help-Seeking Behavior and Treatment Barriers in Anxiety Disorders: Results from a Representative German Community Survey. Community mental health journal, 57(8), 1505–1517. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-020-00767-5 from friends, family, or a mental health professional. Support can help you feel less alone and provide a safe space to talk about your performance anxiety.

Takeaway

It’s important to remember that seeking professional support can be beneficial, especially for those experiencing severe or persistent performance anxiety. With the right tools and support, individuals can learn to perform to the best of their abilities and achieve their goals, even in high-pressure situations.

At A Glance

- Performance anxiety is a type of anxiety triggered by high-pressure situations where an individual is expected to perform in front of others.

- Signs of performance anxiety include physical and psychological symptoms such as rapid heartbeat, sweating, fear of failure, and negative self-talk.

- Causes of performance anxiety include negative past experiences, fear of judgment or failure, pressure to perform, and other biological factors.

- Diagnosis of performance anxiety involves a physical exam, psychological evaluation, and assessment of symptoms and medical history by a mental health professional.

- Treatment for performance anxiety includes therapy, medication, relaxation techniques, and lifestyle changes, and is personalized to the individual’s needs.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How to prevent performance anxiety?

Preparation, practice, and positive self-talk can help prevent performance anxiety.

2. How to treat performance anxiety?

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), medication, and relaxation techniques can be effective treatments for performance anxiety.

3. What triggers performance anxiety?

Performance anxiety can be triggered by fear of failure, negative self-talk, lack of preparation, or negative past experiences.

4. How to break the cycle of performance anxiety?

Breaking the cycle of performance anxiety involves identifying and addressing the root cause of anxiety, practicing coping strategies, and gradually exposing oneself to the feared situation while focusing on positive outcomes.