Seasonal affective disorder, or SAD, is a type of depressive disorder that is related to seasonal changes. It is also commonly known as seasonal depression and major depressive disorder (MDD) with a seasonal pattern.

What Is Seasonal Affective Disorder?

Seasonal affective disorder is a mood disorder that is experienced every year at the same time and is also called summer or winter depression. SAD is considered to be a subtype of depression1 Winthorst, W. H., Roest, A. M., Bos, E. H., Meesters, Y., Penninx, B., Nolen, W. A., & de Jonge, P. (2017). Seasonal affective disorder and non-seasonal affective disorders: results from the NESDA study. BJPsych open, 3(4), 196–203. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjpo.bp.116.004960

Studies 2 Munir, S., & Abbas, M. (2022). Seasonal Depressive Disorder. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK568745/ have shown that SAD gradually decreases one’s energy and can eventually lead to full-blown major depressive disorder. According to research 3 Marqueze, E. C., Vasconcelos, S., Garefelt, J., Skene, D. J., Moreno, C. R., & Lowden, A. (2015). Natural light exposure, sleep and depression among day workers and shiftworkers at arctic and equatorial latitudes. PloS one, 10(4), e0122078. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0122078 , seasonal depression can be commonly observed among people who live further away from the equator, and the symptoms usually resolve in a few months with increased daylight in the spring.

SAD affects various significant aspects of an individual’s life, such as:

- Sleep pattern 4 Anderson, J. L., Rosen, L. N., Mendelson, W. B., Jacobsen, F. M., Skwerer, R. G., Joseph-Vanderpool, J. R., Duncan, C. C., Wehr, T. A., & Rosenthal, N. E. (1994). Sleep in fall/winter seasonal affective disorder: effects of light and changing seasons. Journal of psychosomatic research, 38(4), 323–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3999(94)90037-x

- Biological clock 5 Germain, A., & Kupfer, D. J. (2008). Circadian rhythm disturbances in depression. Human psychopharmacology, 23(7), 571–585. https://doi.org/10.1002/hup.964

- Appetite 6 Yang, Y., Zhang, S., Zhang, X., Xu, Y., Cheng, J., & Yang, X. (2020). The Role of Diet, Eating Behavior, and Nutrition Intervention in Seasonal Affective Disorder: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in psychology, 11, 1451. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01451

- Energy level

- Personal and professional relationships 7 Targum, S. D., & Rosenthal, N. (2008). Seasonal affective disorder. Psychiatry [Edgmont (Pa. : Township)], 5(5), 31–33.

- Sense of self-worth 8 McCarthy, E., Tarrier, N., & Gregg, L. (2002). The nature and timing of seasonal affective symptoms and the influence of self-esteem and social support: a longitudinal prospective study. Psychological medicine, 32(8), 1425–1434. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291702006621

- Self-confidence

- Daily activities 9 Drew, E. M., Hanson, B. L., & Huo, K. (2021). Seasonal affective disorder and engagement in physical activities among adults in Alaska. International journal of circumpolar health, 80(1), 1906058. https://doi.org/10.1080/22423982.2021.1906058

As a result, it can cause several complications that include:

- Lack of interest in social interaction

- School and work-life problems

- Difficulties in performing daily activities

- Suicidal thoughts

- Anxiety and eating disorder

As per research 10 Meesters, Y., & Gordijn, M. C. (2016). Seasonal affective disorder, winter type: current insights and treatment options. Psychology research and behavior management, 9, 317–327. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S114906 , seasonal depression affects around 10% of the global population. The prevalence is completely related to the latitude since it is dependent on the duration of daylight. According to a 2015 study 11 Melrose S. (2015). Seasonal Affective Disorder: An Overview of Assessment and Treatment Approaches. Depression research and treatment, 2015, 178564. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/178564 , women are four times more likely than men to experience this disorder.

SAD vs. Winter Blues

Seasonal affective disorder is more severe than winter blues 12 Targum, S. D., & Rosenthal, N. (2008). Seasonal affective disorder. Psychiatry [Edgmont (Pa. : Township)], 5(5), 31–33. , which is a milder version of this condition. Winter blues refers to a feeling of depression associated with the cold and darkness of winter but it often goes away without treatment.

Another condition that is often confused with the seasonal affective disorder is “holiday depression”, which usually occurs during festivals and vacations.

Read More About Holiday Depression Here

Case Example

Leena had moved to Scotland for her Ph.D. about 3 years ago. Having been born and brought up in the plains of India, she had been used to a warm climate all her life and was still struggling to adjust to the consistently cold temperatures of Edinburgh.

The initial joy of watching the snowfall and skiing on ice had worn out very soon. In fact, with the celsius dropping close to 0 degrees in winter, Leena could barely function. She had never thought she would crave sunlight to such an extent.

For the past three years, Leena would invariably start feeling low, anxious and cranky around November and this would continue until February.

Her colleagues noticed her productivity levels significantly drop around these months. She would also take frequent leaves from work, saying that she was not feeling well. Whenever her friends called her to hang out, she would make up an excuse to stay indoors.

It was safe to say that Leena dreaded winters in Scotland. But this time she decided to talk to someone about it, because she could not afford to slack off at work anymore, and she really wanted to make the best of the season.

After consulting a therapist, she came to learn a great deal about her condition, which was called seasonal affective disorder, and realized that it was possible for her to feel better.

Symptoms Of SAD

Seasonal affective disorder symptoms may range from mild to severe depending on the changes in season, and individual differences. People usually start to experience the symptoms of SAD from October/November till February/March 13 Lingjaerde, O., & Føreland, A. R. (1999). Winter depression with spring exacerbation: A frequent occurrence in women with seasonal affective disorder. Psychopathology, 32(6), 301–307. https://doi.org/10.1159/000029103 ). Although less common, SAD can also occur in summer.

Generally, there are two types of symptoms of seasonal affective disorder depending on the season:

A. Winter symptoms

Most people experience severe symptoms during fall/winter, such as:

- Consistent low mood

- Appetite changes and weight gain 14 Kräuchi, K., & Wirz-Justice, A. (1988). The four seasons: food intake frequency in seasonal affective disorder in the course of a year. Psychiatry research, 25(3), 323–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(88)90102-3

- Changes in sleeping pattern 15 Anderson, J. L., Rosen, L. N., Mendelson, W. B., Jacobsen, F. M., Skwerer, R. G., Joseph-Vanderpool, J. R., Duncan, C. C., Wehr, T. A., & Rosenthal, N. E. (1994). Sleep in fall/winter seasonal affective disorder: effects of light and changing seasons. Journal of psychosomatic research, 38(4), 323–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3999(94)90037-x

- Tiredness or lethargy 16 Rastad, C., Ulfberg, J., & Lindberg, P. (2011). Improvement in Fatigue, Sleepiness, and Health-Related Quality of Life with Bright Light Treatment in Persons with Seasonal Affective Disorder and Subsyndromal SAD. Depression research and treatment, 2011, 543906. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/543906

- Overeating due to carbohydrate craving 17 Wurtman J. J. (1990). Carbohydrate craving. Relationship between carbohydrate intake and disorders of mood. Drugs, 39 Suppl 3, 49–52. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-199000393-00006

- Difficulty in thinking and concentrating

- Feeling sad, cranky, and irritated

- Self-harm thoughts 18 Sit, D., Seltman, H., & Wisner, K. L. (2011). Seasonal effects on depression risk and suicidal symptoms in postpartum women. Depression and anxiety, 28(5), 400–405. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20807

- Social withdrawal 19 Rastad, C., Wetterberg, L., & Martin, C. (2017). Patients’ Experience of Winter Depression and Light Room Treatment. Psychiatry journal, 2017, 6867957. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/6867957

- Reduced sexual interest 20 Lonstein, J. S., Linning-Duffy, K., & Yan, L. (2019). Low Daytime Light Intensity Disrupts Male Copulatory Behavior, and Upregulates Medial Preoptic Area Steroid Hormone and Dopamine Receptor Expression, in a Diurnal Rodent Model of Seasonal Affective Disorder. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience, 13, 72. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2019.00072

- Feeling worthless and guilty 21 Mirzakhani, L., & Poursafa, P. (2014). The Association between Depression and Climatic Conditions in the Iran Way to Preventive of Depression. International journal of preventive medicine, 5(8), 947–951.

- Aches and pains without a medical reason 22 Hawley, D. J., Wolfe, F., Lue, F. A., & Moldofsky, H. (2001). Seasonal symptom severity in patients with rheumatic diseases: a study of 1,424 patients. The Journal of rheumatology, 28(8), 1900–1909.

- Desire for extreme physical activity 23 Drew, E. M., Hanson, B. L., & Huo, K. (2021). Seasonal affective disorder and engagement in physical activities among adults in Alaska. International journal of circumpolar health, 80(1), 1906058. https://doi.org/10.1080/22423982.2021.1906058

- Feeling angry, anxious, and stressed 24 Winkler, D., Pjrek, E., Konstantinidis, A., Praschak-Rieder, N., Willeit, M., Stastny, J., & Kasper, S. (2006). Anger attacks in seasonal affective disorder. The international journal of neuropsychopharmacology, 9(2), 215–219. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1461145705005602

- Crying without any reasonable trigger

- Interpersonal difficulties 25 Chand, S. P., & Arif, H. (2022). Depression. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430847/

B. Summer symptoms

The mild summer symptoms include:

- Feeling depressed most of the day

- Insomnia, hypersomnia, or trouble sleeping 26 Dauvilliers, Y., Lopez, R., Ohayon, M., & Bayard, S. (2013). Hypersomnia and depressive symptoms: methodological and clinical aspects. BMC medicine, 11, 78. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-78

- Poor appetite 27 Rosenthal, N. E., Genhart, M., Jacobsen, F. M., Skwerer, R. G., & Wehr, T. A. (1987). Disturbances of appetite and weight regulation in seasonal affective disorder. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 499, 216–230. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb36213.x

- Anxiety and agitation 28 Winthorst, W. H., Post, W. J., Meesters, Y., Penninx, B. W., & Nolen, W. A. (2011). Seasonality in depressive and anxiety symptoms among primary care patients and in patients with depressive and anxiety disorders; results from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety. BMC psychiatry, 11, 198. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-11-198

- Weight loss 29 Akram, F., Gragnoli, C., Raheja, U. K., Snitker, S., Lowry, C. A., Stearns-Yoder, K. A., Hoisington, A. J., Brenner, L. A., Saunders, E., Stiller, J. W., Ryan, K. A., Rohan, K. J., Mitchell, B. D., & Postolache, T. T. (2020). Seasonal affective disorder and seasonal changes in weight and sleep duration are inversely associated with plasma adiponectin levels. Journal of psychiatric research, 122, 97–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.12.016

- Violent behavior 30 Spies, M., James, G. M., Vraka, C., Philippe, C., Hienert, M., Gryglewski, G., Komorowski, A., Kautzky, A., Silberbauer, L., Pichler, V., Kranz, G. S., Nics, L., Balber, T., Baldinger-Melich, P., Vanicek, T., Spurny, B., Winkler-Pjrek, E., Wadsak, W., Mitterhauser, M., Hacker, M., … Winkler, D. (2018). Brain monoamine oxidase A in seasonal affective disorder and treatment with bright light therapy. Translational psychiatry, 8(1), 198. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-018-0227-2

A 2008 study 31 Targum, S. D., & Rosenthal, N. (2008). Seasonal affective disorder. Psychiatry [Edgmont (Pa. : Township)], 5(5), 31–33. claims that the symptoms of seasonal affective disorder can last for 4 to 5 months in a year. One can experience these symptoms at any age, but they typically start between the age of 18 to 30 32 Melrose S. (2015). Seasonal Affective Disorder: An Overview of Assessment and Treatment Approaches. Depression research and treatment, 2015, 178564. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/178564 . Over time, the symptoms may become severe and affect one’s day-to-day activities.

If you face any of the above seasonal symptoms for two consecutive years, it is recommended that you consult a mental health professional.

Causes Of SAD

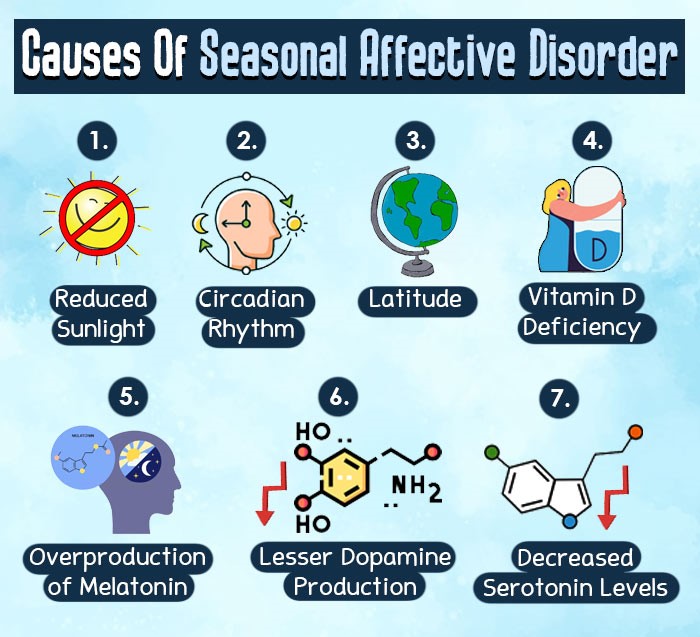

The exact causes of seasonal affective disorder are still unknown, there are some significant factors that can trigger the symptoms, such as:

1. Reduced Sunlight

Seasonal affective disorder is often believed to be associated with reduced exposure to sunlight 33 Kent, S. T., McClure, L. A., Crosson, W. L., Arnett, D. K., Wadley, V. G., & Sathiakumar, N. (2009). Effect of sunlight exposure on cognitive function among depressed and non-depressed participants: a REGARDS cross-sectional study. Environmental health : a global access science source, 8, 34. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-069X-8-34 in the winter months. An important theory 34 Bear, M. H., Reddy, V., & Bollu, P. C. (2021). Neuroanatomy, Hypothalamus. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525993/ claims that reduced daylight may disrupt the functioning of a significant part of the brain called the hypothalamus.

2. Circadian rhythm

Sunlight is extremely essential for several important functions in our body. According to a 2006 study 35 Lewy, A. J., Lefler, B. J., Emens, J. S., & Bauer, V. K. (2006). The circadian basis of winter depression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 103(19), 7414–7419. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0602425103 , as a result of decreased sunlight the biological clock or the circadian rhythm 36 Vitaterna, M. H., Takahashi, J. S., & Turek, F. W. (2001). Overview of circadian rhythms. Alcohol research & health : the journal of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 25(2), 85–93. of the human body often gets disturbed, thus affecting our sleep-wake-cycle, hormones, appetite, and mood. This condition eventually leads to feelings of depression and makes one feel groggy, cranky, anxious, sleepy, and disorientated.

3. Latitude

Research 37 Mersch, P. P., Middendorp, H. M., Bouhuys, A. L., Beersma, D. G., & van den Hoofdakker, R. H. (1999). Seasonal affective disorder and latitude: a review of the literature. Journal of affective disorders, 53(1), 35–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00097-4 suggests that people who live in places that have long winter nights and less sunlight because of the higher altitude are more likely to experience the symptoms of seasonal affective disorder. SAD is more common among the citizens of Canada and Alaska since the sun in these places disappears for months at a time.

The reduced sunlight exposure and the frigid conditions increase the risk of seasonal mood disorder in people of such countries. Contrarily, the sunnier and temperate weather of Florida reduces the risk of being diagnosed with seasonal depression.

4. Overproduction of melatonin

Studies 38 Grivas, T. B., & Savvidou, O. D. (2007). Melatonin the “light of night” in human biology and adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Scoliosis, 2, 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-7161-2-6 have found that the human brain releases melatonin during the night and helps us to fall asleep. Decreased sunlight exposure causes overproduction of melatonin 39 Karami, Z., Golmohammadi, R., Heidaripahlavian, A., Poorolajal, J., & Heidarimoghadam, R. (2016). Effect of Daylight on Melatonin and Subjective General Health Factors in Elderly People. Iranian journal of public health, 45(5), 636–643. hormone in our body. As melatonin regulates our sleep patterns and mood, increased melatonin levels may make us feel sleepy and lethargic at inconvenient times.

5. Lesser dopamine production

Dopamine plays a critical role in light or dark adaptation and has a mutually inhibitory relationship with melatonin 40 Levitan R. D. (2007). The chronobiology and neurobiology of winter seasonal affective disorder. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 9(3), 315–324. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2007.9.3/rlevitan . Increased melatonin often causes lesser dopamine production 41 Zisapel N. (2001). Melatonin-dopamine interactions: from basic neurochemistry to a clinical setting. Cellular and molecular neurobiology, 21(6), 605–616. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1015187601628 in the body. As dopamine develops a sense of pleasure and happiness 42 Bressan, R. A., & Crippa, J. A. (2005). The role of dopamine in reward and pleasure behaviour–review of data from preclinical research. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. Supplementum, (427), 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00540.x in people, decreased dopamine level makes people depressed and emotionally unwell.

6. Decreased serotonin levels

Serotonin 43 Jenkins, T. A., Nguyen, J. C., Polglaze, K. E., & Bertrand, P. P. (2016). Influence of Tryptophan and Serotonin on Mood and Cognition with a Possible Role of the Gut-Brain Axis. Nutrients, 8(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8010056 is a neurotransmitter that affects people’s moods. Reduced sunlight exposure causes a drop in serotonin production. A 2013 study 44 Sansone, R. A., & Sansone, L. A. (2013). Sunshine, serotonin, and skin: a partial explanation for seasonal patterns in psychopathology?. Innovations in clinical neuroscience, 10(7-8), 20–24. says that serotonin deficiency may lead to depression along with other symptoms, including appetite changes, memory problems, drowsiness, and low interest in sexual desire.

7. Vitamin D deficiency

Sunlight is a great source of vitamin D in the human body. A 2015 research paper 45 Patrick, R. P., & Ames, B. N. (2015). Vitamin D and the omega-3 fatty acids control serotonin synthesis and action, part 2: relevance for ADHD, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and impulsive behavior. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, 29(6), 2207–2222. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.14-268342 mentions that vitamin D and serotonin levels are interlinked with each other. During winter, our body experiences vitamin D deficiency followed by decreased serotonin levels and several depression symptoms.

Risk factors for Seasonal Affective Disorder

Apart from causes such as low sunlight etc., certain other factors may also increase the risk of developing SAD, such as:

- Family History 46 Allen, J. M., Lam, R. W., Remick, R. A., & Sadovnick, A. D. (1993). Depressive symptoms and family history in seasonal and nonseasonal mood disorders. The American journal of psychiatry, 150(3), 443–448. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.150.3.443 : Having a family member with a psychological disorder may increase the risk of being diagnosed with seasonal depression.

- Gender 47 Jang, K. L., Lam, R. W., Livesley, W. J., & Vernon, P. A. (1997). Gender differences in the heritability of seasonal mood change. Psychiatry research, 70(3), 145–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0165-1781(97)00030-9 : Seasonal depression is more common among women than men.

- Age 48 Drew, E. M., Hanson, B. L., & Huo, K. (2021). Seasonal affective disorder and engagement in physical activities among adults in Alaska. International journal of circumpolar health, 80(1), 1906058. https://doi.org/10.1080/22423982.2021.1906058 : Younger adults tend to be diagnosed with this mood disorder more than older adults.

- Prior medical history 49 Winthorst, W. H., Roest, A. M., Bos, E. H., Meesters, Y., Penninx, B., Nolen, W. A., & de Jonge, P. (2017). Seasonal affective disorder and non-seasonal affective disorders: results from the NESDA study. BJPsych open, 3(4), 196–203. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjpo.bp.116.004960 of bipolar disorder or major depressive disorder.

Read More About Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) Here

Diagnosis Of SAD

Sometimes, it is extremely difficult to detect seasonal affective disorder even with proper evaluation, as other types of mental disorders may cause similar symptoms.

To be clinically diagnosed with seasonal affective disorder, you would have experienced depressive symptoms during a particular season (summer or winter) for at least more than two consecutive years 50 Munir, S., & Abbas, M. (2022). Seasonal Depressive Disorder. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK568745/ .

A mental health professional, such as a psychologist or a psychiatrist usually takes a detailed history and conducts a mental status examination along with certain psychometric assessments to diagnose SAD. The most common test for screening seasonal depression is the Seasonal Pattern Assessment Questionnaire (SPAQ) 51 Melrose S. (2015). Seasonal Affective Disorder: An Overview of Assessment and Treatment Approaches. Depression research and treatment, 2015, 178564. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/178564 .

Treatment For SAD

Seasonal affective disorder treatment varies depending on your medical history and the severity of your symptoms. It is important to consult a doctor about which treatment is best suited for you. The following are some of the most common beneficial treatments 52 Praschak-Rieder, N., & Willeit, M. (2003). Treatment of seasonal affective disorders. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 5(4), 389–398. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2003.5.4/npraschakrieder for seasonal affective disorder:

1. Bright light therapy

Experts recommend the use of bright light therapy 53 Golden, R. N., Gaynes, B. N., Ekstrom, R. D., Hamer, R. M., Jacobsen, F. M., Suppes, T., Wisner, K. L., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2005). The efficacy of light therapy in the treatment of mood disorders: a review and meta-analysis of the evidence. The American journal of psychiatry, 162(4), 656–662. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.162.4.656 for seasonal affective disorder, as research 54 Campbell, P. D., Miller, A. M., & Woesner, M. E. (2017). Bright Light Therapy: Seasonal Affective Disorder and Beyond. The Einstein journal of biology and medicine : EJBM, 32, E13–E25. suggests that this kind of therapy may be a suitable replacement for the role of natural outdoor light and can even work as an antidepressant. Light therapy can be done either with a lightbox or a dawn simulator.

a. Lightbox

A Lightbox 55 Eastman C. I. (2011). How to get a bigger dose of bright light. Sleep, 34(5), 559–560. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/34.5.559 delivers light that is ten times more intense than normal domestic light. One needs to sit 2 feet away from the lightbox for at least the first hour after waking up in the morning.

A 2009 study 56 Virk, G., Reeves, G., Rosenthal, N. E., Sher, L., & Postolache, T. T. (2009). Short exposure to light treatment improves depression scores in patients with seasonal affective disorder: A brief report. International journal on disability and human development : IJDHD, 8(3), 283–286. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2009.8-283 claims that the full-spectrum light of the lightbox indirectly shines into the eyes and has the ability to significantly reduce SAD symptoms. However, you should not stare directly at the light for a longer time and doing so may cause hypomania 57 Benedetti F. (2018). Rate of switch from bipolar depression into mania after morning light therapy: A historical review. Psychiatry research, 261, 351–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.01.013 in people who also have bipolar disorder.

Read More About Bipolar Disorder Here

b. Dawn simulator

A dawn simulator refers to a device that increases the amount of light in the bedroom. This device can imitate the rising sun in the morning and help you wake up. It gradually increases the light, mimicking sunlight. Studies 58 Leppämäki, S., Meesters, Y., Haukka, J., Lönnqvist, J., & Partonen, T. (2003). Effect of simulated dawn on quality of sleep–a community-based trial. BMC psychiatry, 3, 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-3-14 have found that dawn simulators can help reset one’s circadian rhythm and improve mood.

However, a 2013 study 59 Botanov, Y., & Ilardi, S. S. (2013). The acute side effects of bright light therapy: a placebo-controlled investigation. PloS one, 8(9), e75893. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0075893 has found that light therapy can also cause several side effects, such as agitation or irritability, headaches, eye strain, sleep disorders, blurred vision, and tiredness.

Read More About Sleep Disorders Here

2. Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy 60 Forneris, C. A., Nussbaumer-Streit, B., Morgan, L. C., Greenblatt, A., Van Noord, M. G., Gaynes, B. N., Wipplinger, J., Lux, L. J., Winkler, D., & Gartlehner, G. (2019). Psychological therapies for preventing seasonal affective disorder. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 5(5), CD011270. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011270.pub3 is another effective treatment option for seasonal affective disorder and it is supposed to have long-lasting benefits. One of the most common psychotherapies used to treat seasonal depression is cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) 61 Evans, M., Rohan, K. J., Sitnikov, L., Mahon, J. N., Nillni, Y. I., Lindsey, K. T., & Vacek, P. M. (2013). Cognitive Change across Cognitive-Behavioral and Light Therapy Treatments for Seasonal Affective Disorder: What Accounts for Clinical Status the Next Winter?. Cognitive therapy and research, 37(6), 10.1007/s10608-013-9561-0. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-013-9561-0 .

Read More About Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) Here

3. Medication

If the symptoms of seasonal affective disorder are severe and cannot be treated with light therapy or psychotherapy, prescription medicines can be used for treatment.

Antidepressants 62 Gartlehner, G., Nussbaumer-Streit, B., Gaynes, B. N., Forneris, C. A., Morgan, L. C., Greenblatt, A., Wipplinger, J., Lux, L. J., Van Noord, M. G., & Winkler, D. (2019). Second-generation antidepressants for preventing seasonal affective disorder in adults. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 3(3), CD011268. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011268.pub3 such as bupropion have been found to significantly reduce SAD symptoms. Bupropion is believed to be most effective if taken at the start of the winter before the symptoms appear. However, it is extremely important to know the adverse side effects of antidepressant medication before starting to take them.

Remember to always consult a doctor in case of any problems and never stop medication on your own.

Read More About Antidepressants And Their Side Effects Here

4. Mind-body connection

There are some extremely beneficial mind-body techniques that people often use to deal with seasonal affective disorder. The techniques include:

- Yoga 63 Leskowitz E. (1990). Seasonal affective disorder and the yoga paradigm: a reconsideration of the role of the pineal gland. Medical hypotheses, 33(3), 155–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-9877(90)90165-b

- Mindfulness practice 64 Forneris, C. A., Nussbaumer-Streit, B., Morgan, L. C., Greenblatt, A., Van Noord, M. G., Gaynes, B. N., Wipplinger, J., Lux, L. J., Winkler, D., & Gartlehner, G. (2019). Psychological therapies for preventing seasonal affective disorder. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 5(5), CD011270. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011270.pub3

- Meditation 65 Nussbaumer-Streit, B., Winkler, D., Spies, M., Kasper, S., & Pjrek, E. (2017). Prevention of seasonal affective disorder in daily clinical practice: results of a survey in German-speaking countries. BMC psychiatry, 17(1), 247. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1403-2

- Guided imagery 66 Morgan, A. J., & Jorm, A. F. (2008). Self-help interventions for depressive disorders and depressive symptoms: a systematic review. Annals of general psychiatry, 7, 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-859X-7-13

- Music or art therapy 67 Aalbers, S., Fusar-Poli, L., Freeman, R. E., Spreen, M., Ket, J. C., Vink, A. C., Maratos, A., Crawford, M., Chen, X. J., & Gold, C. (2017). Music therapy for depression. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 11(11), CD004517. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004517.pub3

Read More About Meditation Here

5. Vitamin D treatment

Research 68 Gloth, F. M., 3rd, Alam, W., & Hollis, B. (1999). Vitamin D vs broad spectrum phototherapy in the treatment of seasonal affective disorder. The journal of nutrition, health & aging, 3(1), 5–7. claims that SAD is associated with vitamin D deficiency. Doctors often recommend seasonal depression patients to increase their vitamin D intake through their diet, exposure to sunlight, or vitamin supplements. That said, studies examining the effectiveness of vitamin D treatment have inconclusive findings.

How To Deal With Seasonal Affective Disorder

Besides professional treatment, there are certain other effective ways 69 Melrose S. (2015). Seasonal Affective Disorder: An Overview of Assessment and Treatment Approaches. Depression research and treatment, 2015, 178564. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/178564 to cope with seasonal affective disorder, such as:

- Get as much natural sunlight as possible.

- Follow a healthy lifestyle. Eg: get enough sleep, do regular physical exercise, eat balanced meals, and drink plenty of water.

- Try to spend more time with your loved ones.

- Learn to practice meditation or other mindfulness techniques to manage your stress better.

- If possible, plan a winter or summer vacation based on your seasonal depression pattern.

- Do things that make you happy. Eg: Go to a movie, do gardening, listen to soothing music, take part in religious and social activities, etc.

- Try not to take any important decisions until the depression has lifted.

- Try to stay focused and have faith in the treatment process.

How To Help Someone With Seasonal Depression

If your friend, family member, or partner seems to be suffering from seasonal depression and you’d like to extend a helping hand, here are some things you could do for them:

- Try to be a good listener.

- Encourage them to take professional help and adhere to the treatment plan.

- Take a walk with them, or accompany them in other activities that they might feel too tired to do.

- Contact a support group that will help them deal with their symptoms better.

- Let them know that you love and support them even in the tough times.

- Try to do something special for them that might cheer them up.

Takeaway

Seasonal affective disorder is a type of seasonal depression that people usually experience from the winter till late spring or early summer. People with SAD often experience common depression symptoms according to seasonal changes.

Though it takes a lot of time, most people recover fully with proper treatment and medication. Healthy lifestyle choices can also make it easier for people to deal with the severity of the symptoms.

At A Glance

- Seasonal affective disorder (SAD) is a type of mood disorder associated with seasonal changes.

- People with SAD experience certain mild to severe symptoms, such as daytime fatigue, sadness, social withdrawal, among others.

- Latitude differences, melatonin overproduction, reduced serotonin level, vitamin D deficiency are some of the significant contributing factors of seasonal depression.

- Seasonal affective disorder can be diagnosed with the help of various physical examinations, laboratory tests, and psychological evaluations.

- Doctors often prescribe bright light therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and antidepressant medication for SAD.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Can seasonal depression turn into depression?

Since sunlight is directly associated with serotonin production, people who have SAD due to low levels of serotonin may be at risk of developing severe depression.

2. What do schizophrenia and seasonal affective disorder have in common?

Schizophrenia is a psychotic disorder, whereas SAD is a mood disorder with a seasonal pattern. However, research suggests that people in high latitudes with schizophrenia are prone to developing seasonal affective disorder as well. 70 Doorack, J. E., Allen, J., & Battaglia, J. (2007). Co-occurring SAD symptomatology and schizophrenia at high latitude: a pilot study. International journal of circumpolar health, 66(3), 248–256. https://doi.org/10.3402/ijch.v66i3.18262

3. How to Beat Seasonal Affective Disorder Naturally?

Transcendental meditation, yoga, and other forms of meditation along with a diet rich in vegetables, proteins, complex carbohydrates, and unprocessed foods have been found to be useful for seasonal affective disorder. 71Melrose S. (2015). Seasonal Affective Disorder: An Overview of Assessment and Treatment Approaches. Depression research and treatment, 2015, 178564. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/178564

4. Does vitamin D help with seasonal depression?

Yes. Since a lack of vitamin D can lead to seasonal depression, doctors often recommend it for treatment.

5. When does seasonal depression hit the hardest?

The winter months of December, January and February are considered to be the worst for seasonal depression.

6. How do you prevent seasonal depression?

Due to the predictable nature of seasonal affective disorder, it is relatively easier to prevent it by beginning treatment at the start of the season or planning a vacation to a warmer place during that time.